After the Fog Lifted

Reflections from JPMC 2026 on AI, GLP-1s, and the new physics of biopharma

I. The Alchemists

Last week, the fog lifted from San Francisco, and for four days the city was bathed in a light so sharp it seemed to render everything visible. Those of us who gathered at the Westin St. Francis and across the satellite meetings of the JPM Healthcare Conference (JPMC) moved through this clarity with a steadiness that has been absent in recent years. The post-pandemic uncertainty had finally been metabolized. The zero-interest exuberance had burned off. Something more grounded had taken its place.

I walked the halls, attended the panels, sat through the presentations, and caught up with colleagues. And I found myself wondering not whether we could execute on our plans, but whether any of us fully appreciated what we were building.

The alchemists of our age no longer seek to transmute lead into gold. We seek something far stranger: to feed the disease of the body into a machine and receive, in return, its cure. To make biology computable. To augment the intuition that has driven every medical breakthrough in human history with the silent pattern-matching of neural networks, systems no less voracious than the most relentless human minds in their energy consumption.

Artificial intelligence was the promise echoing through every corridor of JPMC 2026. Eli Lilly and NVIDIA announced a billion-dollar partnership to build a co-innovation laboratory in South San Francisco. The ambition is to have robots conduct experiments in continuous loops, feeding results into models that propose new experiments, which the robots then execute, iteratively, until something works. The goal is not merely acceleration, but transformation: shifting discovery from hypothesis-driven intuition to computational search across vast chemical spaces. It is worth flagging this one for follow up.

Yet I found myself drawn not to these well-capitalized initiatives, but to the margins of the conference. To small teams building foundation models for biology from first principles because I think they understand something that is harder to see from inside large organizations: that artificial intelligence in drug discovery (and development) is not a tool to be bolted onto existing processes. It is a solvent that dissolves them. It demands a fundamentally different way of organizing the labor of understanding life, and the organizational physics of large companies do not always bend easily toward such dissolutions. This is not a criticism, but a structural observation about paradigm shifts. We have all seen how difficult it is to rebuild the ship while sailing it.

There is another class of company I have been watching, and saw again at JPMC with growing unease. These are firms that raised massive VC rounds or went public on the promise of AI-driven discovery, amassed vast data assets, and poured capital into the promise of automation, yet have not produced a single drug of meaningful clinical benefit. Platform stories are seductive precisely because they defer the question of whether the thing actually works. That deferral can last for years. Eventually, the question returns, and when it does, the answer is always binary.

II. The magic number

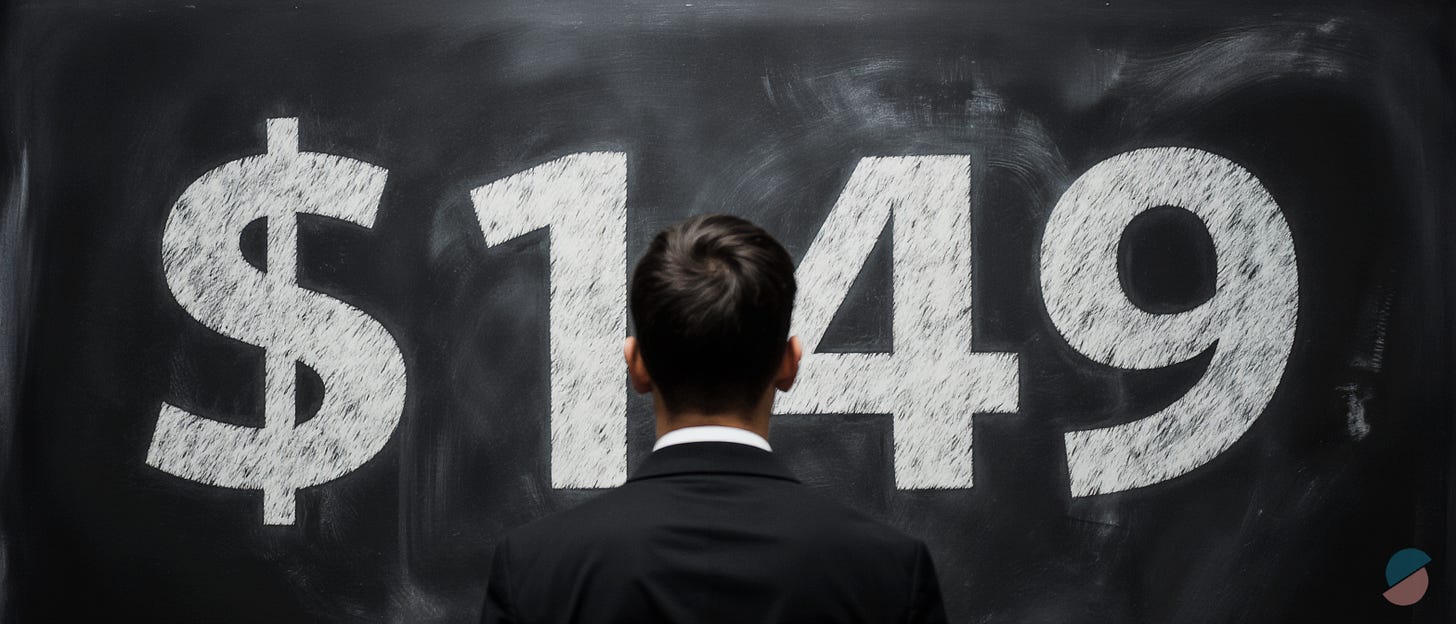

There is a number that lingered over the conference: $149.

This is the price, in dollars, that Eli Lilly proposed for a month’s supply of orforglipron, their oral obesity drug awaiting FDA approval. One hundred and forty-nine dollars. Less than a dinner for two in San Francisco. The cost of a streaming subscription, multiplied across a year.

The number landed with weight because we all understood what it signified. For the first time in the long history of human beings struggling with their own bodies, obesity is becoming a treatable condition at scale. Not through willpower alone. Not through the moral framework that has governed our understanding of weight for centuries. Through chemistry.

The GLP-1 agonists, Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, Zepbound, have already begun to reshape the landscape. But they have done so largely as scarce interventions, expensive and rationed, available to those with good insurance or deep pockets. What Lilly signaled was something different: the intention to manufacture at a scale and price point that could reach everyone who needs it.

The competitive dynamics are intensifying accordingly. Novo Nordisk launched the first oral Wegovy in early January, a week before JPMC opened, and their CEO Mike Doustdar spoke of 2026 as the year oral GLP-1s become accessible to the mass market. Lilly’s orforglipron, if approved, would follow shortly, with the added advantage of no dietary restrictions, a convenience that may prove decisive in a therapeutic class where adherence is everything. Behind them, the field is broadening: Pfizer, having spent roughly $10 billion to acquire Metsera after a bruising bidding war with Novo Nordisk, announced plans for ten Phase III trials in 2026, racing to launch by 2028. Albert Bourla was direct about what this means for a company that some say has struggled since the pandemic: “I don’t want to hear again that there are no catalysts for Pfizer.” Amgen’s MariTide, with its long-acting profile, adds yet another entrant. What was once a duopoly is becoming a crowded field.

On my last evening in San Francisco, waiting for my flight back to New York, I stopped at a restaurant near the gate. When my order arrived, it was far larger than I had expected, one of those portions that reminds you some restaurants operate on a different scale than the human stomach. The woman seated next to me glanced over and smiled. “You’re going to need a long jog after this,” she said.

“No,” I replied, “just a shot of GLP-1.”

She laughed. The man beside her leaned in. “Is this where we’re going?” he asked. “Stabbing ourselves so we can eat?”

It was a joke, but it wasn’t. In that brief exchange at an airport bar, I was the only one carrying the residue of JPMC but the three of us had a shared understanding: that a class of medications developed for diabetes had become, in the span of a few years, a shared cultural reference point for appetite, willpower, and the limits of self-control. The drugs had escaped the conference halls. They had entered the vernacular and become a punchline, which is how you know something has become real.

But sitting there, waiting to board, I found myself thinking not about the competition, or the pricing, or even the punchline. I was thinking about what lies on the other side of it. What happens when the body becomes correctable at scale? When appetite itself can be modulated?

The GLP-1s do not merely suppress hunger; they seem to quiet craving in some deeper register. Patients report diminished interest in alcohol, in gambling, in the compulsive loops that have always been part of human experience. Like so many other phenomena in biomedicine, the mechanism is not fully understood, but the pattern is consistent enough to suggest we are approaching something unique: a pharmacological switch for desire itself.

We had discussed this as a pricing story at JPMC, which of course it is. But it is also something more. We are on the threshold of a new relationship with the human body and we are crossing it in the language of market access and quarterly earnings and in jokes exchanged between strangers at airport gates. Perhaps that is the only way such thresholds get crossed: through commerce, through humor, through the slow normalization of what once seemed impossible.

I suspect we will look back on this moment and recognize that something profound was at stake, even if we lacked the vocabulary to name it at the time.

III. The new Silk Road

On the first day of the conference, AbbVie announced it had paid $650 million, with up to $4.95 billion in milestones to follow, for the rights to a molecule called RC148. It is a bispecific antibody, elegant in design, targeting both PD-1 and VEGF, a combination that may help the immune system fight tumors more effectively while overcoming resistance mechanisms that have limited earlier checkpoint inhibitors. The molecule was developed by RemeGen, in the Chinese city of Yantai.

AbbVie acquired the rights to sell it everywhere except China. The molecule will travel westward and the value will be realized in American and European markets.

This pattern repeated throughout the week. Roche signed deals with MediLink and Hansoh. Novartis partnered with SciNeuro and Zonsen PepLib. Pfizer’s own PD-1/VEGF bispecific came from a Chinese company. The modalities driving oncology’s cutting edge, antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, radioligand therapies, are flowing into Western portfolios from laboratories in Shanghai and Suzhou and Hangzhou. Some of the most promising molecules of the next decade are being conceived in a country with which our political relationship grows more complicated by the year.

And yet, on those same stages, Johnson & Johnson’s Joaquin Duato announced $55 billion in American manufacturing investment. We are simultaneously building walls and extending bridges, investing in domestic infrastructure while deepening our dependence on foreign innovation. I thought of the Silk Road, that ancient network along which goods and ideas traveled in both directions, enriching and destabilizing every civilization it touched. We are building something similar now, with American infrastructure housing global innovation. Capital flowing east, molecules flowing west, and in the middle, a political conversation that has not yet caught up to the scientific reality.

In many ways, we are trying to protect our leadership without severing the arteries that feed it. The balance is delicate. The molecule RC148, born in Yantai, acquired in San Francisco, will soon be infused into the veins of patients with cancer who will never know or, some believe, never need to know where it came from.

This is the topology of the biomedical enterprise in 2026. Whether it can sustain the contradictions building within it is a question that hovered just outside the frame of conversations at JPMC.

IV. The cliff that isn’t

Patent cliffs, like taxes and death, are inevitable. They are the return of a truth that exclusivity allows us to defer: that the ownership of a molecule is temporary, that the profits flowing from a blockbuster drug are a lease, not a deed. The numbers underscored at the conference this year were sobering. More than $200 billion in annual revenue is at risk across the industry through the end of this decade. Merck’s Keytruda, Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Opdivo and Eliquis, AbbVie’s Humira, the drugs that have defined their companies for a decade are losing or will soon lose their protection. The challenge for these companies is navigating the terrain without catastrophic loss of altitude.

Merck’s Rob Davis announced a target of $70 billion in revenue from new growth drivers by the mid-2030s. To reach this number, Merck must essentially replace Keytruda, which accounted for nearly half the company’s revenue last year, with a portfolio of medicines still making their way through development. Davis characterized the coming loss of exclusivity as “more of a hill than a cliff.” This framing is, of course, understandable.

AbbVie offered a different case study, one positioned as being further along in its transition. Having already weathered Humira’s loss of exclusivity in 2023, the company has positioned Skyrizi and Rinvoq to reach $31 billion in combined sales by 2027, effectively replacing what Humira once provided. The execution has been impressive with the share capture faster than analysts expected. Bristol-Myers Squibb is targeting more than ten new medicine launches by 2030. The playbook is consistent across the industry: accelerate the pipeline, pursue strategic acquisitions, build the bridge to the other side before the ground shifts beneath us.

There is nothing cynical in observing that this is difficult. None of us are naive about the challenge as we have seen cliffs before. Some companies have navigated them; others have been diminished. I think what distinguished this year’s presentations was a quality of seriousness, a recognition that the margin for error has narrowed, that execution rather than aspiration will determine outcomes.

The next five years will make the difference clear.

V. The empty chairs

For the second consecutive year, the major health insurers did not attend.

UnitedHealth. CVS Health. Cigna. Humana. Elevance. The institutions that determine which treatments will be reimbursed, which interventions will reach patients, which innovations will translate from clinical trials into clinical practice, they were absent from the Westin St. Francis.

Their absence shaped the conference in ways that were felt by some and mentioned by a few.

We spent four days discussing the elegance of gene therapies, the precision of bispecific antibodies, the transformative potential of artificial intelligence, the coming democratization of obesity treatment. But the partners who will ultimately help determine how much of this reaches patients were elsewhere, engaged in conversations, that one can assume, we cannot be part of.

Needless to say, payers have their own pressures, their own constraints, their own logic. Those who create clinical value and those who adjudicate its economic viability are operating in increasingly distinct spheres. We speak of mechanisms and endpoints. They speak of utilization and total cost of care. The grammar is different and the concerns do not always align and, in many cases, the math bends in their favor.

Let’s consider the tensions embedded in some of the discussions around emerging therapies. A gene therapy that costs $2 million but may cure a disease in a single treatment. An obesity drug that could benefit a hundred million Americans but whose aggregate cost would reshape federal budgets. An Alzheimer’s treatment that might preserve cognition for a few additional months at a price that strains the definition of value. Who pays? On what terms? For how long?

These questions circled JPMC without resolution, because the people best positioned to answer them were not in the room. At some point, these conversations will have to converge. The longer the drift persists, the harder that convergence will become.

VI. After the conference

Stepping out of my last meeting into that improbable January light, I headed for the airport, the weight of the week measured by the stack of business cards in my pocket.

As I walked to my gate, scrolling through #jpm2026 on X, I saw a post claiming this had been the slowest JPM for news in years. In a narrow sense, that was true. There were no transformational acquisitions announced onstage. No single deal dominated the headlines. The mood was industrious rather than triumphant.

But I have learned to distrust the equation of news with significance. Some of the most important shifts announce themselves quietly, through the slow realignment of capital and conviction, through the moment when an industry stops promising transformation and begins the harder work of delivering it.

That is what I observed in San Francisco. An industry that has absorbed recent shocks and emerged more focused. GLP-1 companies building for scale rather than scarcity. AI partnerships moving from press releases to physical laboratories. Startups pursuing genuinely novel biology at the margins, largely unnoticed by the main stage but potentially more consequential than anything presented upon it. The quiet integration of Chinese innovation into Western portfolios. Patent cliffs enforcing a discipline that might otherwise have been deferred.

JPMC 2026 lacked the speculative electricity of earlier years. The sense that anything might be announced at any moment has given way to something more measured. Whether this reflects maturity or simply a different phase of the cycle is unclear. Perhaps the two are inseparable.

What I know is this: the fog has lifted. Many have seen themselves clearly and they have chosen execution over spectacle. What we build from here, whether the bridges hold, whether the science delivers, whether the economics align, will be the work of the next decade.

The conference ended. We returned to our responsibilities. The winter sun continued to illuminate the city, indifferent to what had been discussed within it.

Brilliant and beautiful. GLP-1 writ large: Here and everywhere, seems the question is whether we will bring purpose and value to the technology, or allow the tech to define us.