The Interoperability Illusion

How America Built a $36 Billion Digital Health Infrastructure That Can’t Talk to Itself

"The world as we have created it is a process of our thinking. It cannot be changed without changing our thinking." Albert Einstein

Why I’m writing this

At this year’s JPM healthcare conference, I met a new generation of AI startups take the stage, convinced they would transform medicine through technology, including what we call real-world data (RWD). They have the algorithms, the compute, and a new class of investors eager to back them. They know the first generation of RWD companies underdelivered, but chalk it up to a lack of AI. Now that the tools exist, they figure, the hard part is over. After all, how bad can the data infrastructure really be? Meanwhile, physicians are more disillusioned with health IT than I’ve ever seen them. And nations are racing to build AI advantages in critical sectors like healthcare and defense, a race the United States will not win with a data infrastructure that can’t reliably move a patient record across town.But the real reason I’m writing this is patients, patients whose treatment decisions are being made with incomplete information because their data is trapped in systems that won’t talk to each other. This essay is for them. For us.I. The machinist

"Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets." W. Edwards Deming

There is a fax machine in your doctor’s office. It is 2026, and there is a fax machine, humming, warm, loaded with thermal paper or perhaps the inkjet variety, and it is one of the most reliable ways to transmit your medical records from one institution to another.

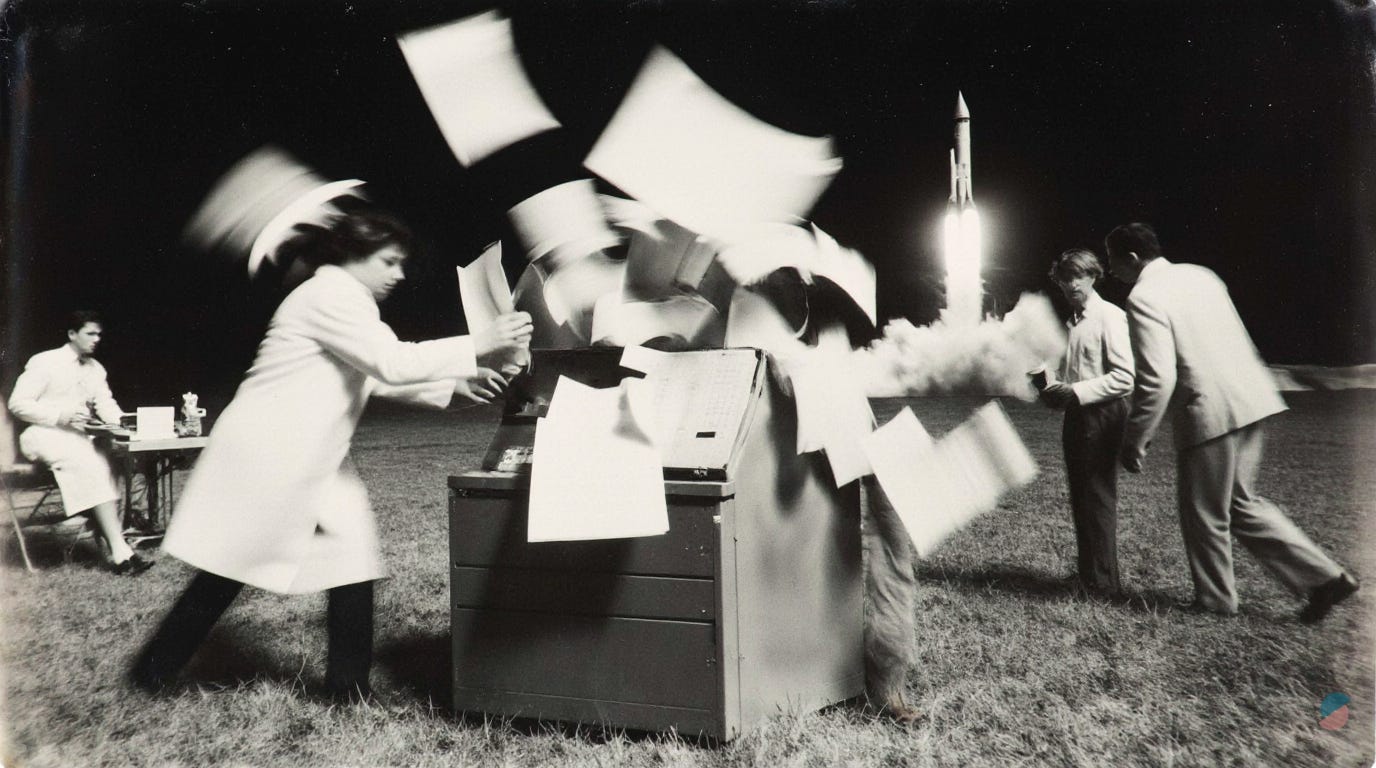

This is not a failure of technology. We split the atom in 1945. We sequenced the human genome decades ago. We put a supercomputer in everyone’s pocket and connected it to a global information network that can settle a financial transaction in milliseconds across twelve time zones. The inability of American healthcare to move a patient record from Hospital A to Hospital B is not a technology problem at all. It is a choice. More precisely, it is the accumulated residue of thousands of deliberate choices made by people and institutions that benefit from the friction they created.

I’d like to tell you how I think this happened, why no one is fixing it, and what it would actually take to change. I’m going to be direct about this because the usual discourse around health IT interoperability is drowned out by euphemisms like “challenges,” “opportunities,” and “stakeholder alignment.” The reality is uglier and more interesting than the conference keynotes and panel discussions suggest.

II. The original sin

“The best way to predict the future is to invent it.” Alan Kay

To understand why health IT interoperability is so hard, we have to understand what electronic health records (EHRs) were actually built to do. And it wasn’t medicine.

The modern EHR is, at its architectural core, a billing system. The data model is organized around encounters, procedure codes, and diagnosis codes, the atomic units of revenue capture. Clinical utility was bolted on afterward, like a sunroof added to a submarine. When a physician tells you that Epic feels like it was designed by accountants, that’s because, functionally, it was. The system’s primary job is to generate clean claims that Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial payers will reimburse. Everything else, clinical decision support, care coordination, patient communication, and research, is a secondary function running on infrastructure that was never designed for it.

This wasn’t inevitable. It was a calculated policy choice. When the HITECH Act of 2009 authorized roughly $36 billion in incentive payments to drive EHR adoption, the program, branded “Meaningful Use,” prioritized speed and billing. Get systems installed. Get providers clicking. Get data captured in some electronic format so we can move past paper charts and illegible handwriting. The standards that the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT certified against, HL7 version 2, the Consolidated Clinical Document Architecture, were what existed at the time. They were imperfect, everybody knew they were imperfect, and the calculation was that imperfect adoption now was better than perfect adoption never.

And here is what happened next: hospitals and health systems spent billions implementing these systems, building workflows around them, training staff on them, and integrating them into revenue cycle operations. By the time the standards proved catastrophically inadequate, and they proved inadequate quickly, the switching costs were astronomical. You cannot easily redo the foundation of a house that people are actively living in, especially when the mortgage is $500 million and the CFO’s career depends on the investment being judged a success.

So we locked in. And what we locked into was a fragmented archipelago of proprietary systems optimized for billing, sold by a handful of dominant vendors to captive institutional buyers, with just enough interoperability to satisfy certification requirements and not one byte more.

III. The vendor calculus

"It is difficult to get a person to understand something when their salary depends upon them not understanding it." Upton Sinclair

Data lock-in and interoperability issues are not bugs in the EHR business model. They are the business model.

The dominant EHR vendor today understood early and with remarkable clarity that if data exchange worked smoothly across their own network and everything else was painful, the rational move for any health system was to join their ecosystem. They built interoperability within a walled garden, a brilliant competitive strategy that has been devastating for the broader ecosystem. They built a company worth billions on the insight that in healthcare, data gravity is the ultimate moat.

Other vendors operate on the same principle with varying degrees of sophistication. They sell to C-suite executives and IT procurement committees, not to the doctors and nurses who use the systems fourteen hours a day. The buying decision is driven by brand reputation, institutional relationships, revenue cycle features, and, critically, the promise that “everyone else is on this platform.” Once a health system has committed, they’re locked in for a decade or more. The competitive pressure that drives consumer software: make a bad app and users delete it tomorrow, simply does not exist.

This is why EHR interfaces are, to put it plainly, terrible. Four thousand clicks per shift with critical information buried in nested tabs. Notes that are not clinical communications but medicolegal billing artifacts with some patient information embedded inside. The vendor doesn’t need to make the daily experience good. They need to make the demo impressive and the revenue cycle reliable. The end users, the ones wearing scrubs and making life-and-death decisions, have no leverage in the transaction.

The vendors will, of course, speak eloquently about their commitment to interoperability. They will point to FHIR API implementations, app marketplaces, and participation in standards bodies. What they will not tell you is that true interoperability, the kind where a patient’s complete longitudinal record flows seamlessly between competing systems, where any authorized application can read and write clinical data without friction, would commoditize their product and destroy their competitive advantage. Every vendor in the market understands this. Their interoperability strategies are carefully calibrated to satisfy regulatory requirements while preserving the moat.

IV. The standards paradox

"The nice thing about standards is that you have so many to choose from." Andrew S. Tanenbaum

People outside health IT often assume that interoperability problems are simply a matter of agreeing on standards. If everyone spoke the same language, the thinking goes, the data would flow. This is true in the same way that world peace would solve most geopolitical problems, technically correct and practically useless.

Health IT has standards. It, in fact, has a bewildering abundance of standards. HL7 version 2 for messaging. HL7 version 3 for the overengineered replacement that largely failed. FHIR for the modern web-native approach that’s still maturing. C-CDA for clinical document exchange. DICOM for imaging. ICD-10 for diagnoses. SNOMED CT for clinical terminology. LOINC for laboratory observations. RxNorm for medications. MedDRA for adverse events. X12 for administrative transactions. NCPDP for pharmacy. The list continues.

The problem is not the absence of standards. The problem is threefold.

First, the standards are developed by consensus among the same stakeholders who benefit from the current dysfunction. It has been suggested that health data standards organizations are heavily influenced by the vendors they are supposed to be standardizing. Standards are designed to accommodate existing vendor architectures rather than to force vendors toward better ones. The fox is consulted extensively on henhouse security policy.

Second, the existing standards are implemented inconsistently. HL7v2 is perhaps the most instructive example: it is ubiquitous, ancient, and so flexible that two “compliant” HL7v2 feeds can look completely different. Compliance with the standard tells you almost nothing about whether two systems can actually exchange useful data. It’s as if two people both “speak English” but one is using 18th-century legal terminology and the other is texting in abbreviations.

Third, healthcare data is genuinely, irreducibly complex. A single oncology patient encounter might generate structured vital signs, free-text clinical notes, pathology reports with semi-structured findings, DICOM imaging studies, genomic sequencing results, medication orders mapped to multiple drug vocabularies, and billing codes, all of which need to be interoperable. No single standard covers all of this gracefully. And when you add the dimension of time, the need to assemble a coherent longitudinal record across decades, institutions, and data formats, the complexity becomes formidable.

FHIR, the newest and most promising standard, is a genuine improvement. It’s web-native, resource-based, and far more intuitive than its predecessors. But it is still maturing, its coverage of complex clinical domains like oncology and genomics is uneven and, crucially, it can be implemented in ways that technically satisfy the specification while providing minimal practical utility. The vendors have become very skilled at this kind of compliance theater.

V. The absent patient identifier

"For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong." H.L. Mencken

The United States has no national patient identifier.

When you go to a hospital, you are assigned a medical record number. It is unique to that institution. When you go to a different hospital, you get a different number. When someone tries to assemble your records across institutions, for care coordination, for research, for your own understanding of your health, they have to figure out that Patient 4729183 at Johns Hopkins and Patient 8291047 at Mass General are the same person.

This matching is done probabilistically, using name, date of birth, Social Security Number fragments, address, and other demographic data. It fails at meaningful rates, estimates range from 8 to 12 percent, and it fails disproportionately for common names, recent immigrants, married women who’ve changed their names, people who’ve moved, and patients whose information was entered with typos. These are not edge cases. This is a substantial fraction of the population.

Why don’t we have a patient identifier? Because in 1998, Congress inserted a single line into an appropriations bill prohibiting the Department of Health and Human Services from spending any funds to develop one. This provision has been renewed every year since, driven originally by privacy concerns that, while understandable in the 1990s, have aged poorly in a world where we carry GPS-enabled devices that track our every movement and willingly hand our biometric data to smartphone manufacturers.

Twenty-seven years. The same appropriations rider. Renewed automatically, year after year, because no member of Congress wants to be the person who voted for a “national health ID” and because the political cost of fixing it exceeds the political benefit. Meanwhile, patient matching errors cause duplicate records, missed allergies, repeated tests, incorrect medication histories and, in cases that rarely make headlines but are documented in the patient safety literature, preventable harm.

You cannot build reliable interoperability when you cannot reliably identify whose data you are looking at. Everything else (the APIs, the standards, the governance frameworks) is built on sand without this foundation. And Congress, in its infinite wisdom, has made it illegal to even attempt to solve this problem with federal funds.

VI. Why no one fixes it

"The major problems in the world are the result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think." Gregory Bateson

If you’ve read this far, you might be wondering: given that the problems are well understood, the technology to solve them exists, and the human cost is real, why doesn’t someone do something about it?

The answer is that almost everyone who has the power to fix it is making money from it being broken. The vendors are very profitable and they have no rational economic incentive to make data portable. The health systems are locked in. The CIO who just spent half a billion dollars on an EHR implementation is not going to the board to say it needs to be replaced. The CFO cares that revenue cycle is functioning. Neither is losing sleep over whether a community oncologist can see imaging from the academic center across town. They all mean well but they have to be flawless at what their job descriptions demand of them.

The consultants and integrators thrive on the chaos. An entire industry exists to sell duct tape for systems that don’t connect properly. Interoperability middleware, data normalization services, interface engines, HIE infrastructure, this ecosystem would lose its reason to exist if EHRs worked well out of the box. They are, in effect, a tax on dysfunction, and they have no interest in shrinking the tax base. Paraphrasing a colleague, this is a classic example of rent-seeking behavior.

Congress won’t act because health IT is not a voter issue. The vendor lobbies spend generously and frame every proposed regulation as a threat to innovation or patient safety. The information blocking provisions in the 21st Century Cures Act took years of political effort to pass in 2016, and its enforcement has been anemic. The Office of Inspector General (OIG) has brought essentially zero meaningful cases. The rules have teeth on paper and gums in practice.

CMS, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, could be the most powerful lever. They control the money. Medicare represents roughly 40 percent of hospital revenue. If CMS said, “Starting in 2028, Medicare reimbursement requires certified FHIR API endpoints with validated data quality on the United States Core Data for Interoperability standard,” the entire industry would move in a few months. They’ve done versions of this with other requirements and it works. But CMS is risk-averse, stretched thin operationally, and terrified of being blamed if a mandate causes disruptions at hospitals. So they nudge instead of shove.

And clinicians, the people who suffer most directly from the dysfunction, who spend hours on workarounds and phone calls and, yes, faxes, are too burned out to fight. They’re working sixty-hour weeks, dealing with staffing shortages and the administrative burden the EHR itself contributes to. The AMA and specialty societies publish position papers about usability that nobody with procurement authority reads.

The patients, meanwhile, have little idea what’s happening. They are never told why their records didn’t transfer, or why their doctor is asking them to repeat their medication list, or why the imaging CD from the outside hospital can’t be read. They blame the front desk or assume this is just how healthcare works. There is no consumer uprising because the dysfunction is invisible to the people it harms most.

VII. The political impossibility

"In politics, nothing happens by accident. If it happens, you can bet it was planned that way." Franklin D. Roosevelt

A new presidential administration, any administration, is unlikely to fix this. Not because the problem is unsolvable, but because it is politically unrewarding.

Health IT interoperability has no natural constituency. When an administration walks in with finite political capital and a short window to deploy it, they spend it on things voters care about: drug prices, insurance coverage, opioids, the crisis of the moment. “Fix EHR interoperability” does not poll well. It is invisible infrastructure, the policy equivalent of sewer modernization. It matters enormously, but there is no ribbon to cut.

This has been called a bipartisan failure by many insiders because of a structural trap: the benefits of interoperability are diffuse and long-term (better care coordination, faster research, reduced waste, lives saved) while the costs are concentrated and immediate. Force real interoperability and the vendors lose revenue and lobby hard, the hospitals face implementation costs and complain to their senators, and some things break during the transition and make the news. No politician gets credit for the slow accumulation of benefit. But they do get blamed for the disruption.

VIII. What would actually work

"You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete." Buckminster Fuller

I don’t believe there is a single solution but there is a sequence of moves that could shift the equilibrium, if anyone had the will to make them.

CMS must leverage the checkbook. Tie Medicare reimbursement to real, validated, tested interoperability, not checkbox certification, but demonstrated data exchange with measurable quality metrics. The EHR industry will scream about burden and patient safety, which is exactly what they said about every prior CMS mandate, and then they’ll comply, because forty cents of every hospital dollar is non-negotiable.

Enforce the information blocking rules. OIG needs to bring visible, consequential enforcement actions against those who obstruct data flow. Not warnings or corrective action plans. Financial penalties that appear in earnings reports. One or two high-profile cases would change industry behavior overnight.

Eliminate the patient identifier ban. This twenty-seven-year-old policy needs to be phased out. It doesn’t require a national ID card; a voluntary digital credential, a hashed identifier system, a federated matching service. The technical options are numerous. What’s required is for Congress to remove the appropriations rider and let HHS actually work on the problem.

Separate the data layer from the application layer. Health data should live in a standardized, portable, patient-controlled layer. The EHR becomes an application that reads from and writes to that layer, but it does not own the data. Think of how your phone number ports between carriers. ONC’s TEFCA framework gestures in this direction, but it’s voluntary and slow. Making it mandatory would fundamentally restructure the market, because suddenly vendors would have to compete on the quality of their software rather than the stickiness of their data.

Let AI restructure the interface. This is perhaps the most realistic near-term path. If ambient AI, clinical scribes, intelligent summarization, and decision support become the primary way clinicians interact with patient data, the EHR’s terrible interface becomes less relevant. The EHR shrinks to a billing and persistence engine, which is what it was always best at. The risk is that the incumbent vendors build or acquire these AI capabilities and keep them proprietary, extending the walled garden into the next generation. The countermove is to ensure that AI tools connect to data via open, standardized APIs rather than vendor-controlled integration points.

VIII. What I believe

"The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it." Flannery O'Connor

I’ve spent my career at the intersection of clinical research, technology, and the regulatory frameworks that govern them. I’ve watched the gap between what technology makes possible and what our infrastructure allows grow wider with each passing year. I’ve seen researchers spend months assembling datasets that should have taken days. I’ve seen clinical trials delayed because imaging data couldn’t be standardized across sites. I’ve sat in meetings where smart people discussed interoperability as though it were primarily a technical challenge, as though the right standard or the right API would unlock everything.

It won’t. The technology is not the hard part. We move petabytes of financial data across the globe in real time. We stream video to billions of devices simultaneously. We build AI systems that read medical images with superhuman accuracy. The idea that we cannot move a patient’s medication list from one hospital to another is, on its face, absurd.

What we have is an incentive problem wrapped in a political problem wrapped in an institutional culture that has learned to tolerate extraordinary dysfunction. The system isn’t broken. It is working exactly as designed for the people who designed it.

But I’m optimistic, and here’s why.

Lately, I’ve been noticing something new: a critical mass of smart people who understand that the current clinical trial paradigm is unsustainable and that the path forward runs through real-world data. Not as a supplement to randomized trials, but as a fundamental shift in how we determine whether drugs work, a world where initial regulatory approval is based on safety and where real-world evidence generated continuously from routine clinical care becomes the primary mechanism for establishing our understanding of a drug’s effectiveness over time. That world doesn’t just benefit from interoperable data. It requires it. When real-world efficacy determination becomes the standard, every data silo becomes a bottleneck with a dollar sign attached to it. The incentives that currently preserve fragmentation would reverse.

As my colleague Andrew Lo likes to say, don’t fight cancer, put a price on its head. The same principle applies here. Two decades of fighting for interoperability through panel discussions, standards committees, and voluntary frameworks produced, at best, incremental progress. But if we shift efficacy determination to the real world, if the ability to generate reliable evidence from clinical practice becomes the basis for commercial success in drug development, then interoperable data stops being just a public good that everyone applauds and no one funds. It becomes a competitive asset that the market will build, whether the incumbents cooperate or not.

Our clunky EHRs will keep going until the cost of their existence exceeds the cost of replacing them. I believe we are approaching that threshold. The generation of founders, investors, clinicians, and regulators now entering the arena may be the ones who finally tip it, not by petitioning the system to change, but by building something that makes the old model untenable.

But until then, somewhere, right now at this very moment, a fax machine is humming. And someone’s life may depend on whether it goes through.

Thank you for such a thoughtful piece Sean.

What strikes me is that interoperability isn’t just about moving records.

It’s about enabling longitudinal intelligence.

If data truly flowed — across institutions, time, and modalities — we could begin to measure not just encounters, but trajectories.

Right now, our infrastructure supports transactions. It does not support compression of disease arcs.

AI layered on fragmented, encounter-based data risks industrializing inefficiency faster.

AI layered on interoperable, longitudinal data could do something different — identify inflection points earlier, support upstream intervention, and shift the objective from managing decline to altering course.

Interoperability is the substrate.

The real question is what we build on top of it.