The Ghost in the Statistical Machine and the Illusion of the Average Patient

A Brief History of Precision in Medicine and FDA's Evolution

I. The summoning

On a spring morning in 1747, twelve sailors aboard HMS Salisbury became unwitting participants in an unprecedented act: James Lind, ship’s surgeon, divided them into pairs with the cold efficiency of a mathematician partitioning equations. To some he gave citrus; to others, cider, vinegar, seawater, sulfuric acid, or a mysterious concoction of garlic and mustard seed. By the voyage’s end, those who had eaten oranges and lemons walked. The others continued their grotesque metamorphosis: teeth loosening from blackened gums, blood seeping through skin like rust through iron.

Lind had performed something special: he had isolated a single variable in the chaos of human suffering. In doing so, he discovered not merely a cure for scurvy, but a methodology that would reshape the architecture of medical knowledge itself. He had invented the controlled trial, giving birth to the Age of Controlled Empiricism. Yet in that same moment of illumination, he conjured into existence a phantom that would haunt biomedicine for the next three centuries: the specter of the Average Patient, a statistical ghost that exists nowhere except in the aggregate, an abstraction that lives only in tables and spreadsheets.

The Average Patient does not exist, yet its statistical ghost has served us well. It has saved millions. But it has also exacted a heavy price: the systematic erasure of the particular in service of the universal.

II. The regulatory fortress

The ghost would find its most powerful guardians not in hospitals, but in the machinery of federal government. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), born in 1906 from a cocktail of patent medicine scandals and Upton Sinclair’s1 stomach-turning prose, spent its first decades concerned primarily with adulteration and mislabeling: asking whether the bottle contained what the label promised, not whether what it promised was true.

The transformation occurred in 1962, against the backdrop of thalidomide. Across the Atlantic, children were being born with phocomelia: flipper-like limbs where arms should be, because a sedative given to pregnant mothers had crossed the placental barrier with devastating effects. The United States largely avoided this tragedy, thanks to FDA medical officer Frances Oldham Kelsey’s firm skepticism. However, the fear of what could have happened led to the Kefauver-Harris Amendments,2 which for the first time required manufacturers to prove not only safety but also efficacy through “adequate and well-controlled investigations.”

Thus was erected the regulatory fortress: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial as the gold standard, indeed the only standard of medical truth. The logic was unassailable. If we demand that drugs work for the average patient in the controlled artifice of a trial, we protect the public from snake oil and corporate malfeasance. We trade the Country Doctor’s intuition for the statistician’s rigor. We exchange anecdote for p-values, opinion for effect sizes, the particular for the generalizable.

The FDA’s mission became the guardianship of “internal validity”: ensuring that observed effects were real and not artifacts of bias or chance. What we gained in certainty, however, we lost in applicability. Trial populations were homogeneous by design: adults aged 18-65, generally healthy except for the condition under study, willing and able to provide consent, adherent to complex protocols. The elderly were excluded. The very sick were too risky. Children were protected. The pregnant were forbidden. Racial and ethnic minorities were underrepresented; women were systematically excluded until the 1990s.

We had purchased internal validity at the cost of “external validity”: the ability to generalize findings beyond the narrow confines of the trial itself. We could prove a drug worked for the ghost, but we struggled to predict whether it would work for the grandmother with polypharmacy, the child with a rare variant, the patient whose ancestry and environment had shaped their biology in ways our trials never captured.

The fortress stood for decades. Until cracks began to appear.

III. The epistemology of the mean

To understand the depth of this problem, we must excavate the mathematical bedrock upon which the clinical trial rests. At its foundation lies the Central Limit Theorem,3 that miraculous promise that the mean of a sufficiently large sample will approximate the population mean. Francis Galton called regression to the mean “the most beautiful law in all statistics.” R.A. Fisher gave us the mathematics of randomization and the analysis of variance. These tools allowed us to extract signal from noise, to see the ghost emerge from the data.

But biology is not obligated to respect our statistical conveniences. In fact, like the greater universe, it is completely unaware of and indifferent to them. A normal distribution assumes that variation is random noise around a true central value: that patients deviate from the mean the way bullets scatter around a bullseye, their differences the product of measurement error and uncontrolled variance.

What if the “noise” is the signal? What if what we have been calling variation is actually heterogeneity: meaningful biological differences that determine whether a patient thrives or dies on a given therapy?

Let’s examine this in terms of music. In my 2002 medical school thesis on physiological harmonics (link above), I suggested that health is not a point on a number line but a key signature: a relationship among variables that together create concordance. Disease is not deviation from a mean; it is modulation into dissonance. A heart in normal sinus rhythm plays in predictable, consistent time; atrial fibrillation is the dissolution into arrhythmic chaos. In the composition Perpetual Drift, I traced how a simple heart block, first-degree and barely symptomatic, can degrade through second-degree Mobitz II into complete dissociation, then spiral into the polymorphic terror of torsades de pointes. Each transition is a key change, a harmonic shift.

The traditional RCT measures the average volume of the crash, but it is deaf to the melodic progression that preceded it. It aggregates a thousand different songs, squeezes them into a mean, and calls the result music.

IV. The molecular revolution and the epistemic crisis

Then came the genome. In 2000, the completion of the Human Genome Project promised a new epoch: personalized medicine, tailored to the individual’s genetic code. The reality proved more labyrinthine. We discovered that human genetic variation was both more extensive and more subtle than anticipated. Single nucleotide polymorphisms, single-letter typos in the three-billion-letter text of the genome, number in the millions. Some change everything; most do nothing; many interact in ways we still cannot predict. In truth, we know very little.

But in rare diseases, especially those of Mendelian origin, the promise crystallized. When a condition results from a single genetic error, a nonsense mutation in MECP2 causing Rett syndrome, a trinucleotide expansion in HTT causing Huntington’s disease, the old paradigm shatters. If there are only a few in the world with a particular mutation, how do you design a randomized trial? Who comprises the control arm? How many must die untreated to satisfy our epistemic demands?

The question is ethical vertigo: the recognition that our evidentiary standards, built to protect the many, have become obstacles to saving the particular. A barrier to the very essence of precision medicine.

V. A signal in the noise

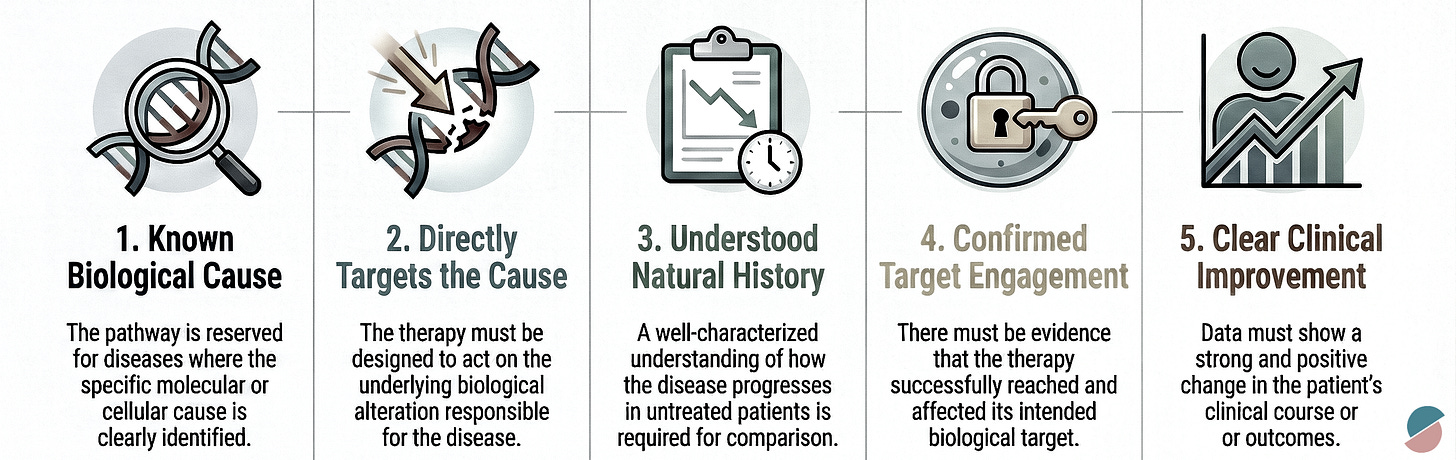

In November 2025, the FDA published a brief sounding board in the New England Journal of Medicine. Co-authored by Commissioner Martin Makary and Vinay Prasad, it bore the understated title “FDA’s New Plausible Mechanism Pathway.” Within its three pages lay something remarkable, though its significance is easy to misread. This was not the arrival of a new era. It was something more modest and more important: a signal, a first step, a door cracked open onto a landscape we have only begun to map.

The catalyst was Baby K.J., a male neonate who presented within 48 hours of birth with carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) deficiency. The enzyme defect prevented his body from processing dietary protein, causing ammonia to accumulate to neurotoxic levels. Without intervention, the natural history was clear: progressive brain damage with each hyperammonemic crisis, punctuated by hospitalizations, until the child grew large enough for liver transplantation, if he survived that long.

Genetic sequencing identified the specific biallelic mutations responsible. A team designed a bespoke therapy: lipid nanoparticles loaded with guide RNA and messenger RNA encoding an adenine base editor, targeted to repair that exact genetic error. The FDA processed a single-patient Investigational New Drug application in one week. Three consecutive doses were administered. The child’s ammonia levels normalized. He began tolerating dietary protein. The need for nitrogen-scavenger medications declined.

There was no control group. There were no randomized comparators. There was no placebo arm of doomed infants sacrificed to statistical rigor. The patient served as his own control, measured against the well-characterized natural history of untreated disease.

The pathway means that when a manufacturer demonstrates success across several consecutive patients with different bespoke therapies using the same platform technology, the FDA may grant marketing authorization not for each individual therapy, but for the platform itself: the base-editing system, the nanoparticle delivery vector, the cell therapy process. Subsequent therapies targeting different mutations can then be deployed under that umbrella approval.

Baby K.J. lived. That matters infinitely. But we must be careful not to mistake a beginning for an ending, a seed for a harvest. The pathway is not the transformation we need. It is evidence that transformation has become thinkable, that the regulatory architecture we inherited from the 20th century can evolve. What we do with that evidence will determine whether this moment becomes a turning point or a footnote.

VI. The work ahead

The pathway shows us what is possible, but it does not create what is necessary. Between the vision of precision medicine and its realization is an enormous expanse of unglamorous, essential work: the construction of infrastructure, the development of methods, the cultivation of relationships. None of this can be accomplished by fiat alone. All of it requires collaboration.

Natural history studies must be conducted with the same rigor we once demanded of control arms. If a person’s only comparator is the natural history of their condition, that history must be characterized with precision. Who will fund these studies? Who will ensure they capture the diversity of patients who will eventually receive treatment?

Post-marketing surveillance must be robust and durable. When a gene-editing therapy modifies a patient’s genome, the effects may unfold over years or decades. Off-target edits may have consequences that are invisible at first. Immune responses may evolve. This demands real-world data systems that persist long after the initial commercial push has faded, follow-up mechanisms that track patients across moves and insurance changes, and analytical methods capable of detecting true signals in noisy environments.

There is a temptation, when new regulatory flexibility appears, to view it as a concession extracted from reluctant gatekeepers. This framing is both historically inaccurate and strategically misguided. The pathway emerged not despite the FDA but because of it, because the agency recognized that existing frameworks could not accommodate what biology now makes possible.

Working shoulder to shoulder with regulators means something specific. It means investing in the infrastructure they need to evaluate novel evidence types. It means transparency about what we know and what we do not. It means participating in the hard work of defining standards and clinically validated endpoints, even when they constrain short-term commercial interests. It means treating post-marketing requirements not as burdens but as expressions of responsibility for the patients who receive our therapies in the real world.

VII. The N of 1 at scale

The phrase “precision medicine” has always contained a paradox. Medicine operates at scale: systems that treat millions, insurance schemes that pool risk across populations, research programs that aggregate data for statistical power. Precision implies the particular: this patient, this mutation, this moment. How do we reconcile mass with customization, the industrial with the artisanal?

Appropriately validated platform technologies can create precision at scale. A single base-editing system can address dozens of monogenic diseases. An antisense platform can target hundreds of pathogenic transcripts. An adoptive cell therapy framework with standardized manufacturing can be reprogrammed for different tumor antigens. An AI-enabled decision support system can recommend combination therapies calibrated to individual tumor genomics, adjusting its recommendations as each patient’s response unfolds. The marginal cost of designing the next therapy, once the platform is established, becomes manageable. Mass customization, the manufacturing paradigm that transformed industries from automobiles to consumer electronics, becomes applicable to medicine.

But manufacturing is the easy part. Harder is the epistemological challenge: generating evidence for therapies that may each be used in only a handful of patients, yet must collectively demonstrate safety and efficacy. This is the problem of the N of 1 at scale: proving that a methodology works across many single-patient applications.

The solution is not in more sophisticated trial designs conducted in isolation from clinical practice, but in dissolving the boundary between research and care altogether. When we embed these platform technologies into routine care across health systems, when every infusion center and community oncology practice and academic medical center operates on shared infrastructure, something remarkable becomes possible: we learn from each patient we treat. We intervene, we observe, we feed what we learn back into the system, and we improve. The next patient benefits from every patient who came before.

This is the vision of the learning health system applied to precision medicine. Each treated patient becomes not merely a recipient of care but a contributor to collective knowledge. The child with CPS1 deficiency whose ammonia normalizes after base editing teaches us something about editing efficiency, about immune response, about durability of effect. That knowledge, captured systematically, informs the treatment of the next child with a different urea cycle disorder. The oncology patient whose tumor responds unexpectedly to a novel combination reveals patterns that the AI system incorporates, refining its recommendations for future patients with similar molecular profiles.

The cycle must be continuous: intervene, observe, learn, improve, intervene again. Each iteration sharpens our understanding. Each patient encounter generates data that flows back into decision support systems, natural history registries, safety surveillance databases. The platform improves not through occasional version updates but through constant refinement, the way a recommendation algorithm learns from every interaction.

VIII. The convergence

We have been here before, or thought we were. The first generation of real-world data platforms promised transformation and delivered fragmentation: incompatible systems, inconsistent data standards, analytics that could not distinguish signal from noise. Electronic health records captured billing codes rather than biology. Registries accumulated data that no one analyzed. The infrastructure for learning health systems was built, but the learning never materialized.

What is different now is the convergence. Over a decade of investment in health information technology has created, despite its failures, a substrate upon which something better can be built. Genomic sequencing costs have collapsed a thousandfold. Artificial intelligence can capture structured data as an ambient scribe and extract patterns from datasets too vast and too complex for human comprehension. Regulatory science has evolved to accommodate novel evidence types. And the spirit of American innovation, that restless ingenuity that has always driven our most consequential advances, has turned its attention to the architecture of medical knowledge itself.

The pieces of the puzzle are coming together. Interoperable data standards are emerging. Cloud computing enables aggregation across institutions. Machine learning can control for confounding in observational data, detect safety signals in real time, identify patients likely to respond to specific therapies. The FDA has signaled willingness to accept evidence generated outside traditional trials. Payers are beginning to recognize that paying for data generation creates value. Patients, increasingly, demand to be partners rather than subjects.

Of course, the technical capability to build learning health systems does not ensure the political will to fund them, the institutional commitment to sustain them, or the social trust to make them acceptable. But the possibility that seemed utopian a decade ago now seems achievable. The question is no longer whether we can build systems capable of learning from the N of 1 at scale, but whether we will.

IX. The digital country doctor

What might come out of this work is a synthesis: a return to the philosophy of the Country Doctor, the obsession with the individual patient, the deployment of clinical judgment in the context of intimate knowledge, but equipped with tools s/he could never have imagined.

The 19th-century physician knew their patients across decades, accumulated pattern recognition through experience, and developed an intuitive sense for prognosis. But their knowledge was shallow vertically. They could palpate the spleen but not sequence the JAK2 mutation causing its enlargement. They could percuss the chest but not image the ground-glass opacities of pulmonary fibrosis or predict progression through algorithms trained on millions of CT scans. Their judgment was informed by dozens of patients; ours can be informed by millions.

The vision of 21st-century precision medicine inverts the Country Doctor’s limitations: vast mechanistic knowledge, genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, coupled with computational tools to interpret it at the resolution of the individual. Each patient becomes not a deviation from the population mean but a unique trajectory through a high-dimensional state space, their biology a specific point that can be characterized, modeled, and targeted.

In oncology, this transformation is becoming visible. “Lung cancer” has decomposed into a taxonomy of molecular species: EGFR-mutant adenocarcinoma responds to osimertinib; ALK-rearranged disease to alectinib; tumors with high PD-L1 expression to pembrolizumab; KRAS G12C mutations to sotorasib. The average survival of “lung cancer patients” becomes a meaningless statistic; what matters is the natural history of this molecular subtype in this patient given this intervention.

X. Coda: the seed and the soil

James Lind summoned the statistical ghost aboard HMS Salisbury out of necessity. To prove that citrus prevented scurvy, he needed to demonstrate average efficacy. The ghost served us well for nearly three centuries. It gave us antibiotics and vaccines, chemotherapy and antiretrovirals and targeted therapies. It protected millions from ineffective or dangerous treatments. It established the principle that medical claims must be proven, not merely asserted.

But the ghost was always a compromise, a necessary simplification in an era when we could measure populations but not individuals, when we could characterize diseases by symptoms but not mechanisms, when we could statistically aggregate but not molecularly dissect.

We are beyond that era now. The genome is sequenced. The proteome is being mapped. Computational biology can model individual trajectories through state space. Gene editing can target single-nucleotide variants. The epistemological justification for the ghost has dissolved.

What remains is the ethical question: Having gained the capability to treat the particular, do we have the wisdom to wield it responsibly? Can we accelerate access without sacrificing safety? Can we embrace precision without encoding bias? Can we validate platforms without forcing dying patients to wait for statistical significance?

The regulatory signals we have received do not answer these questions. They ask them. They are seeds, planted in soil we have only begun to prepare. Whether they grow into the transformation precision medicine requires depends on what we do next: the infrastructure we build, the methods we develop, the partnerships we forge, the commitments we sustain.

The goal is not to force every patient into the same key signature, but to understand the particular song each person plays and to intervene not with the blunt instrument of population averages, but with the precision of a composer who knows that changing a single note, correcting a single base pair, can transform dissonance into resolution, silence into symphony, the inexorable trajectory toward death into the improbable grace of continued life.

We are learning, three centuries after Lind, that the choice was never between the aggregate and the particular, between rigor and compassion, between population health and individual salvation. The choice is whether we have the courage to begin the work that this moment demands: to labor alongside our peers and regulators to build systems capable of learning from the N of 1 at scale, to accept that the pathway we have been given is not a destination but a departure point.

Baby K.J. lived. That matters infinitely. But what matters more, in the long arc of medical history, is what we make of his survival: whether we treat it as a singular miracle or as the first note of a symphony we must now learn to compose, together.

The music has begun. Let us all rise to play our part.

Upton Sinclair (1878–1968) was a central figure in the “muckraking” era of investigative journalism. His 1906 novel, The Jungle, was intended to highlight the exploitation of workers, but its graphic descriptions of unsanitary conditions in Chicago meatpacking plants, including diseased livestock and contaminated products, horrified the public. This widespread outrage, combined with a decline in meat sales and subsequent federal investigations, directly pressured President Theodore Roosevelt and Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act in 1906. These laws established the regulatory framework that ultimately became the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1930.

The 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments transformed the FDA’s regulatory mandate in response to the thalidomide tragedy, which caused severe birth defects in thousands of children globally. These amendments fundamentally shifted the burden of proof to manufacturers, requiring them to demonstrate not only the safety of a drug but also its efficacy through “adequate and well-controlled investigations”. This established the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial as the “gold standard” for medical truth in American regulation.

The Central Limit Theorem is a fundamental principle of probability theory stating that the distribution of sample means will approximate a normal distribution (a “bell curve”) as the sample size becomes larger, regardless of the population’s actual distribution. In the context of clinical trials, this theorem allows us to extract a statistical “signal” from the “noise” of individual patient data, effectively giving rise to the concept of the Average Patient. However, critics argue that relying on this mean can obscure meaningful biological heterogeneity, where the “noise” is actually a critical signal for personalized treatment.

Great piece Sean the road begins.

This is an unusually clear and serious piece. The way you trace the lineage of the “Average Patient” — from Lind through Kefauver-Harris to the modern regulatory fortress — gets at something many of us sense but rarely articulate this precisely: that the statistical ghost was a necessary compromise, not an error, and that biology has now outgrown it.

I was especially struck by your insistence that the current regulatory signals are seeds, not solutions. Treating cases like Baby K.J. as miracles rather than signals would be the real failure of imagination. The challenge, as you frame it, isn’t whether we can act on the particular, but whether we can build systems that learn responsibly from the N of 1 without abandoning rigor or trust.

This feels like a departure point rather than a conclusion — and I hope the conversation around it widens.