The Rational Road to Inefficiency

A Game-Theoretic Analysis of Government Performance

In the midst of the current debates about government efficiency, a crucial insight often gets lost: the problem isn't usually the people—it's the game itself. During my tenure at the US Food and Drug Administration, I witnessed firsthand how some of our nation's brightest minds found themselves in a system where inefficiency can become the only rational choice. I believe this paradox—smart people making seemingly irrational decisions—demands analysis through the lens of game theory, which reveals how individual rationality can produce collective irrationality.

The conventional narrative about government inefficiency typically follows a predictable script: bureaucrats are portrayed as either incompetent or indifferent. Yet this caricature often crumbles upon close examination. Federal agencies consistently attract accomplished professionals from prestigious institutions and industry leadership positions. These individuals bring not only technical expertise but also genuine dedication to public service. The analytical challenge, therefore, lies not in explaining a talent deficit, but in understanding how institutional structures can transform individual capability into collective underperformance.

Understanding Government Behavior Through Game Theory

Game theory1 provides a rigorous framework for analyzing why capable individuals within government can sometimes produce suboptimal outcomes. At its core, game theory examines how individuals make decisions when their choices affect each other's outcomes. The classic illustration is the prisoner's dilemma: two suspects are interrogated separately, each facing a choice to remain silent or testify against the other. If both stay silent, they receive light sentences. If both testify, they receive medium sentences. But if one testifies while the other stays silent, the betrayer goes free while the silent one receives a heavy sentence. Despite cooperation yielding the best collective outcome, the rational choice for each individual is to betray—creating a worse outcome for both.

This framework can illuminate decision-making across complex organizations where multiple stakeholders interact. Within federal agencies, career professionals, appointed officials, budget analysts, and oversight bodies each make choices that ripple through the system. Like participants in the prisoner's dilemma, these capable individuals may find their rational choices aggregating into outcomes that serve neither their intentions nor the public interest, despite—or perhaps because of—their careful individual calculations.

The Quarterly Budget Paradox

The budgetary system in government exemplifies this dynamic. In the private sector, efficient resource management typically leads to positive outcomes: reduced costs improve profit margins, enabling reinvestment or return of capital to shareholders. Corporate officers are expected to be careful stewards of shareholder capital, their performance measured by tangible metrics of value creation.

Government budgeting often operates under very different incentives. For example, agencies operate under the "use it or lose it" phenomenon. As each quarter ends—particularly the fourth quarter—departments must spend their entire allocation or risk budget reductions in subsequent periods. This can create a perverse incentive where efficient resource management becomes professionally dangerous while wasteful spending becomes rational. Government contractors know this well.

The FDA Case Study: Theory Meets Reality

The FDA’s digital transformation efforts offer compelling empirical evidence supporting modern innovation frameworks. During my tenure at the agency, I spearheaded the INFORMED Initiative, which included an effort to digitize premarket safety reports—a cornerstone of the FDA’s regulatory authority. Premarket safety monitoring, one of the agency’s most critical functions during drug development, is conducted under the Investigational New Drug (IND) process. This regulatory framework requires sponsors to report critical safety signals during clinical trials, generating thousands of reports that demand meticulous analysis.

Our digitization project promised to deliver dual, transformative benefits: saving approximately 500 full-time equivalent hours each month while significantly enhancing the agency’s ability to detect critical safety signals across a vast reporting ecosystem. The initiative’s importance and early success were recognized through publication in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery and garnered strong support from senior FDA leadership, including the Commissioner. Technical feasibility was demonstrated through successful pilot programs, with major biopharmaceutical companies volunteering to test and support the system—an impressive milestone, given the industry’s traditionally cautious approach to regulatory changes.

However, despite its promising start and potential to transform a core FDA function, the initiative’s momentum stalled after my departure from the agency. This outcome, when viewed through the lens of game theory, becomes more understandable. The INFORMED Initiative had temporarily reshaped the incentives around the project to prioritize innovation, a critical shift in an area characterized by high regulatory stakes. Once this protective framework was removed, stakeholders reverted to risk-averse strategies driven by the inherent incentive structure. Game theorists would describe this as an asymmetric risk-reward scenario: championing innovation in a high-stakes regulatory environment provided limited personal gain while exposing individuals to significant professional risk. Similar to the dynamics of the prisoner’s dilemma, where self-preservation overrides collective benefit, stakeholders gradually defaulted to maintaining established processes rather than advocating for change.

This challenge was compounded by the intricate nature of safety monitoring responsibilities, which required coordinated efforts across multiple stakeholders. Success depended on simultaneous cooperation, previously facilitated by the INFORMED framework. Once that mechanism dissipated, uncertainty around universal participation likely led stakeholders to favor risk-averse decisions, prioritizing the status quo over innovation. The inherent complexity of regulatory processes amplified this coordination challenge, further entrenching resistance to change.

The trajectory of this initiative underscores a vital lesson: sustainable innovation in core regulatory functions requires more than technical feasibility and leadership support. It demands institutionalized mechanisms to realign and maintain incentives over the long term. As the volume and complexity of safety reporting continue to grow, this lesson remains critically relevant for the FDA and other regulatory agencies navigating similarly high-stakes environments.

Nash Equilibrium in Government Operations

This pattern reflects what Nobel laureate John Nash described as an equilibrium state—a scenario where no individual actor can improve their position by unilaterally altering their strategy. In the context of budget management, for example, a department head who spends less than their allocation may inadvertently signal that their budget can be reduced in future cycles. Observing such outcomes, other department heads often prioritize fully utilizing their budgets, reinforcing a consistent pattern of resource expenditure.

This dynamic is especially noticeable in the tendency of departments to increase spending near the end of a fiscal year. While this behavior may seem inefficient from an external perspective, it aligns with the incentives embedded in the system, where unspent resources can lead to reduced allocations in subsequent periods. Viewed through the lens of game theory, this behavior represents a Nash equilibrium: individual actors, operating within the constraints of the system, make rational decisions that collectively reinforce existing patterns. This underscores the importance of carefully designed incentive structures to balance short-term resource management with long-term strategic goals.

The Measurement Mirage

Current performance metrics in government agencies present unique challenges when compared to the private sector. In business settings, success is often measured by clear outcomes such as profit margins, market share, or customer satisfaction. Government agencies, however, operate in a context where such direct metrics are less applicable, frequently defaulting to process-oriented measurements. This can sometimes lead to what is described as a principal-agent problem, where the objectives of the agents (government officials) may not perfectly align with the broader goals of public service.

For example, government performance reviews often prioritize adherence to established procedures, completion of required trainings, and the effective management of existing processes. While innovation and efficiency improvements are broadly encouraged, these factors are less likely to carry significant weight in formal evaluations. Consequently, professional advancement often hinges on mastering established processes rather than driving systemic improvements or fostering creative solutions.

At the organizational level, similar patterns emerge. Success is often evaluated through metrics such as the number of regulations or guidances issued, the speed of document processing, or the completion of mandated reports. While these measurements are straightforward and quantifiable, they may not always capture the full extent of the agency’s contribution to public value. These observations highlight the importance of aligning performance metrics with meaningful outcomes, ensuring that both individual and organizational goals reflect the broader mission of serving the public effectively.

Strategic Reform: Redesigning the Game

Understanding government inefficiency through game theory can illuminate paths to meaningful reform. I believe the solutions lie not in just changing player behavior within the existing game, but in fundamentally restructuring the game itself. Success requires transforming current zero-sum scenarios into positive-sum opportunities where individual and collective interests align.

Corporate performance metrics typically cascade from organizational objectives to individual responsibilities, creating clear lines of accountability. Government agencies can adopt similar frameworks by implementing rigorous outcome-based metrics that focus on measurable impact rather than process adherence. This means moving beyond traditional compliance measures to track efficiency gains, service delivery improvements, and resource optimization.

The FDA premarket safety pilot program demonstrated this principle in microcosm. When we temporarily altered incentive structures—allowing teams to reinvest a portion of their efficiency gains—innovation flourished. This created a positive-sum game, where individual success aligned with organizational improvement.

Restructuring Budget Incentives

The current budgetary system requires particular attention. The use it or lose it dynamic can create tragedy of the commons, where rational individual behavior depletes collective resources. Reform requires transforming this zero-sum game into a positive-sum scenario.

Consider a revised model: Instead of penalizing efficiency with budget reductions, agencies could retain a portion of demonstrated savings for reinvestment in improved service delivery. This can lead to a virtuous cycle where efficiency generates resources for further improvement. Such an approach would mirror how successful corporations manage capital allocation, treating taxpayer dollars with the same fiduciary care shareholders expect from corporate officers.

Creating Competitive Pressure

Market dynamics provide another crucial lesson. Private sector efficiency often stems from competitive pressure—companies must optimize or risk losing market share. While government agencies rarely face direct competition, artificial pressure can be created through performance benchmarking, public dashboards, and cross-agency comparisons.

This transparency creates reputational incentives, where public scrutiny motivates improved performance. Recent expansions of telework policies across government agencies demonstrate how lack of such pressure can prioritize bureaucratic convenience over operational efficiency.

Implementation Strategy

Successful reform requires careful sequencing. Game theory suggests starting with what's known as focal points—areas where stakeholder interests naturally align. Initial efforts should target obvious inefficiencies where improvement benefits all parties. Success in these areas builds momentum for broader reform.

The FDA's digitization initiative offers instructive lessons. Despite clear benefits, it was not fully implemented because it challenged too many existing incentive structures simultaneously. A more successful approach might have started with smaller, departmental-level changes, creating demonstrable wins before attempting system-wide transformation.

From Theory to Practice

Game theory reveals how current government inefficiencies emerge from rational responses to misaligned incentives. The solution lies in restructuring these incentives to align individual rationality with collective efficiency—a challenge now being tackled at an unprecedented scale.

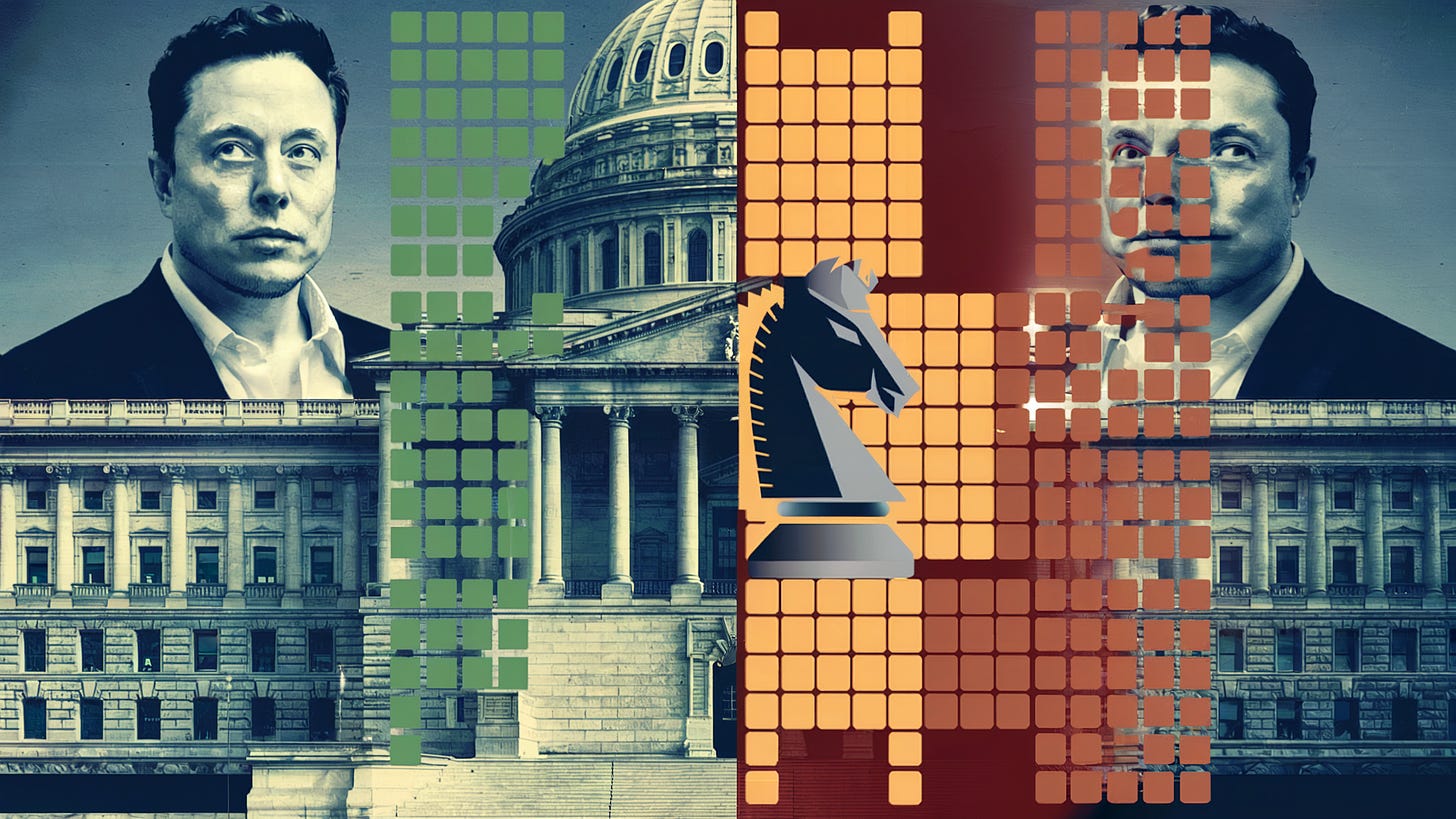

The recently launched Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, represents the first systemic attempt in recent years to reduce government spending through efficiency gains. By setting a deliberate expiration date of July 4, 2026—the 250th anniversary of American independence—DOGE has further created a forcing mechanism, where limited time focuses effort and resources on achieving concrete results.

Success within this compressed timeframe requires moving beyond traditional reform approaches to fundamental redesign of institutional incentives. The initiative's focus on measurable outcomes and structural reform, rather than incremental changes, suggests a sophisticated understanding of the game-theoretical principles that govern organizational behavior. When institutional frameworks make efficiency the dominant strategy for individual actors, public sector performance can finally match the considerable capabilities of its personnel.

This represents not merely a theoretical possibility but an achievable objective through thoughtful institutional design. By changing the rules of the game—not just the players—we can create a system where doing the right thing and doing the smart thing become one and the same.

As citizens, public servants, and stakeholders in America's future, we all share a profound interest in the success of these efficiency efforts. Whether we work within government or outside it, whether we craft policy or are affected by it, governmental efficiency would benefit us all. The question is not whether we can afford to succeed in this endeavor—it's whether we can afford to fail.

Game Theory Concepts and Their Applications in Government

Core Concepts

Nash Equilibrium

A state where no individual actor can improve their position by unilaterally changing their strategy. In government contexts, this can explain why inefficient practices persist - individual actors are making rational choices given the constraints of the system.

Prisoner's Dilemma

A scenario where two rational actors might not cooperate even when it's in their best interest to do so. Key characteristics:

If both cooperate, both receive moderate benefits

If both defect, both receive moderate penalties

If one defects while the other cooperates, the defector receives maximum benefit while the cooperator receives maximum penalty

The rational choice for each individual leads to worse collective outcomes

Principal-Agent Problem

A situation where the objectives of agents (e.g., government officials) may not align perfectly with the broader goals they're meant to serve. This misalignment can lead to suboptimal outcomes even when individual actors are acting rationally within their incentive structure.

Tragedy of the Commons

A situation where rational individual behavior leads to the depletion of shared resources. In government, this manifests in budget management where departments may overspend to protect future allocations, depleting collective resources.

Applied Concepts

Zero-Sum vs. Positive-Sum Games

Zero-Sum: Situations where one party's gain equals another's loss (common in current government budget allocation)

Positive-Sum: Scenarios where multiple parties can benefit simultaneously (goal of reformed government processes)

Asymmetric Risk-Reward Scenarios

Situations where potential gains are limited but potential losses are significant. This explains risk-averse behavior in government innovation, where champions of change face significant professional risk with limited personal benefit.

Coordination Problems

Scenarios requiring multiple stakeholders to act simultaneously for success. In government, this manifests in complex initiatives requiring cooperation across different departments or agencies.

Focal Points

Areas where stakeholder interests naturally align, serving as starting points for reform efforts. These represent opportunities where change can begin with minimal resistance.