The Simulator’s Dilemma

Reflections on AI in Drug Discovery

I. RG7112

In the winter of 2018, a molecule designated RG7112 entered a Phase I trial for acute myeloid leukemia. Its journey to human testing had been immaculate by every computational standard. The compound bound its target, MDM2, a protein that suppresses the tumor guardian p53, with exquisite selectivity. The binding affinity was in the low nanomolar range. Off-target interactions were minimal. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion (ADMET) predictions were favorable. The molecule had been designed using structure-based methods refined over two decades, drawing on thousands of crystallographic structures and millions of data points. Every in silico checkpoint had been passed with honors.

But the molecule failed in humans, although not for lack of target engagement. It bound MDM2 precisely as predicted and successfully raised p53 levels. But dose-limiting thrombocytopenia and neutropenia emerged, narrowing the therapeutic window to the point of clinical futility. The human body, confronted with this molecularly perfect intervention, revealed complexities the models hadn’t captured: MDM2’s role in hematopoietic homeostasis, the cascade of p53-dependent effects on normal tissues, the margin between therapeutic and toxic that existed only in patients, not predictions.

This was not an AI discovery. RG7112 predated the current wave of machine learning platforms. But it exemplifies a persistent gulf: the distance between binding a target and curing a disease, between computational elegance and clinical efficacy.

For AI drug discovery platforms, the business model today follows a predictable descent:

If you don’t have a drug, you sell a “vision.” If you don’t have a vision, you sell “data.” What we cannot sell, what remains stubbornly unsellable and difficult to achieve, is certainty about human response.

Yet this is only half the story. The same general period that produced RG7112’s failure also produced imatinib’s triumph in chronic myeloid leukemia, the first checkpoint inhibitors in solid tumors, and the early GLP-1 agonists that would eventually transform diabetes and obesity treatment, and several targeted therapies in oncology. The question is not if drug discovery can succeed; clearly it can, and spectacularly, but rather what distinguishes success from failure, and how artificial intelligence can change that equation.

II. The productivity collapse that refused solutions

Eroom’s Law, Moore’s Law in reverse, describes the observation that the number of new drugs approved per billion dollars of R&D spending has halved approximately every nine years since 1950. By 2010, the inflation-adjusted cost of bringing a new molecular entity to market had reached approximately $2 billion; recent estimates place it over $3 billion. Development timelines have extended from 8-10 years in the 1990s to 10-15 years today.

This occurred while every enabling technology improved exponentially. High-throughput screening can now test millions of compounds in a matter of weeks. Genomics costs dropped from $100 million per genome to under $1,000. Structural biology advanced from laborious X-ray crystallography to cryo-EM structures determined in days. CRISPR enabled precise genetic manipulation. Single-cell sequencing revealed cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution.

The productivity declined anyway.

The orthodox explanation invokes “low-hanging fruit, ” that simple, tractable diseases have been addressed, leaving only complex, multifactorial conditions. This is partially true but insufficient. I think the more fundamental issue is architectural: drug discovery built itself on reductionist assumptions that worked brilliantly for certain problem classes and failed systematically for others.

Example: Imatinib for CML worked because the disease is driven by a single genetic lesion, the BCR-ABL fusion, whose inhibition is sufficient for therapeutic benefit in many patients. Checkpoint inhibitors succeeded because blocking PD-1/PD-L1 released a pre-existing anti-tumor immune response. GLP-1 agonists exploited well-understood incretin biology. In each case, the biological hypothesis was correct and reasonably complete. The target was necessary, often sufficient, and modulation produced predictable effects. But the reductionist paradigm was also aided by fortunate accidents: semaglutide’s dramatic impact on weight loss exceeded predictions based on incretin pharmacology alone, and sildenafil found its primary therapeutic use in erectile dysfunction rather than the cardiovascular indications for which it was designed. These serendipitous discoveries remind us that even our most rational frameworks benefit from careful observation of what actually happens in patients. Reductionism works, when the biology is simple, linear, and the target is genuinely causal. And when we are paying close attention to the happy accidents.

But these successes, including the happy accidents, are exceptions that prove the rule. For every imatinib, there are dozens of molecules that hit their targets precisely as designed and failed to produce clinical benefit. When biology is networked, adaptive, and compensatory, the target-centric paradigm fails.

The problem is not that we lack targets. We have tens of thousands from genomics, proteomics, and functional screens. The problem is that the concept of“target” is an incomplete abstraction.

A kinase inhibitor may block its intended target with beautiful selectivity, but the pathway adapts, alternative routes activate, or the target proves dispensable in the complex homeostasis of an organism.

The map, the target, is not the territory but we are obssessed with optimizing maps.

III. The first AI wave: pattern recognition as meaning

When computational methods entered drug discovery in the 1980s and 1990s, they arrived as pattern recognizers. Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models learned correlations between molecular features and biological activities. Molecular docking algorithms predicted binding poses by optimizing shape complementarity and energetic favorability. Virtual screening ranked millions of compounds by predicted affinity.

These methods produced genuine value in narrow domains. They accelerated lead optimization, flagged likely toxicity issues, and guided medicinal chemistry decisions. But they shared a structural limitation: they were trained on data from artificial, reductive systems, isolated enzymes, cell lines passaged into biological abstraction, and binding assays divorced from physiological context.

The implicit wager was that sufficiently sophisticated pattern recognition would converge on truth. That enough data about molecular properties would encode the rules governing therapeutic efficacy. This assumption proved to be too optimistic and fundamentally incorrect.

Correlation, however massive the dataset, does not substitute for causal understanding of systems that operate through feedback, redundancy, and adaptation.

By 2010, the first wave had plateaued. Models predicted ADMET properties with increasing accuracy, but drug approval rates remained flat. As it turned out, the bottleneck was not computational chemistry. It was biological uncertainty that the models did not address because they did not represent it.

IV. What AI drug discovery actually does today

The current generation of AI platforms operates under different branding but often with similar constraints. The language has shifted from “virtual screening” to “generative design,” “foundation models,” and “phenomics,” but the core capabilities remain bounded.

And here, a necessary acknowledgment: today’s AI systems excel at multidimensional optimization within known constraints.

Given a target with validated biology, modern machine learning can navigate the tradeoff space between potency, selectivity, metabolic stability, and synthetic accessibility with remarkable efficiency. It identifies molecules that thread the needle between competing demands, high brain penetration but low cardiac liability, sub-nanomolar binding but acceptable solubility, novel IP space but synthetic tractability. This is by no means trivial. This is engineering of high sophistication and it accelerates medicinal chemistry substantially.

But optimization is not discovery. Engineering assumes the blueprint is correct. Discovery is the search for the blueprint itself.

The problematic conflation occurs when platforms present optimization capabilities as solutions to the causation problem. Let’s examine, for example, the phenomics approach: imaging cells under tens of thousands of perturbations, genetic knockdowns, compound treatments, and disease states, generating petabytes of imaging data. The claim is that patterns in cellular morphology reveal “new biology,” that AI can infer mechanism from phenotype, and that correlation at scale becomes insight.

The technical achievement is real but the biological inference is unproven. A morphological rescue in engineered osteosarcoma cells is not therapeutic benefit in humans. The domain shift is not a minor technical gap; it is the central problem. An immortalized cell line on plastic lacks immune infiltration, tissue architecture, metabolic gradients, and the thousand other contextual factors that determine whether a perturbation matters in patients.

This pattern repeats across platforms: impressive scale, genuine technical sophistication, and a logical leap from data volume to biological understanding that the data does not support. When drug programs extend beyond projected timelines (as they must, because biology has not been compressed), the narrative shifts to partnerships, tool licensing, and infrastructure. The platform becomes a service. Revenue is recorded. The drug, if it eventually materializes, is validation. If it fails, the platform was still “valuable for insights.”

This is not cynicism but an observation of a very rational business strategy in the face of irreducible uncertainty. But it should be named clearly for what it is: monetizing the tool, not the cure.

V. The core mismatch: interpolation in a world that demands extrapolation

The fundamental tension in AI-powered discovery is purely mathematical.

AI, in its current paradigm, excels at interpolation within learned manifolds. Drug discovery requires extrapolation into unobserved biological regimes.

Every model, whether a neural network predicting binding affinity or a computer vision system classifying cellular phenotypes, learns a mapping from input to output based on training examples. Reliability degrades as the distance from the training distribution increases. This is not a bug to be fixed. This is the very structure of inductive inference.

Chemistry risk is, in principle, containable within this framework. The space of drug-like molecules is vast but bounded. The physics governing molecular interactions, hydrogen bonding, π-stacking, hydrophobic effects, and electrostatics are known. The body’s major metabolic enzymes are enumerated. Given sufficient training data on related chemical series, AI makes reasonably reliable predictions about ADMET properties, off-target binding profiles, and synthetic routes.

But biology risk is categorically different.

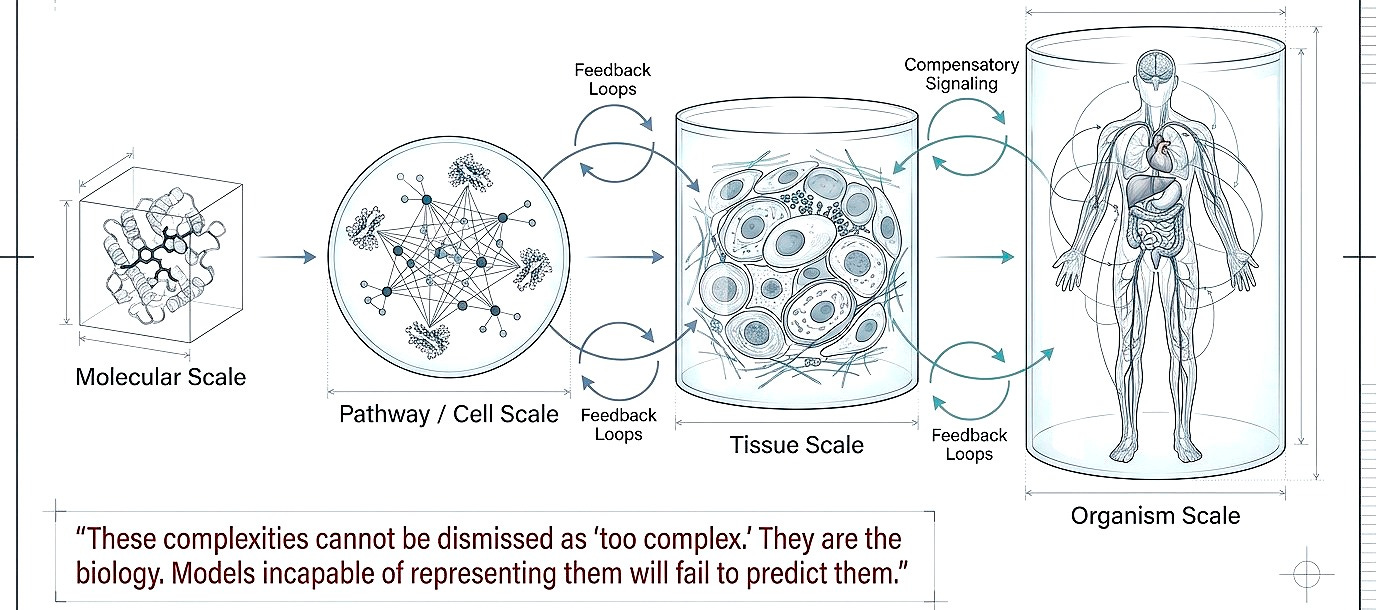

The real challenge is not whether a molecule will bind its target, that is increasingly predictable. It is whether modulating that target will produce therapeutic benefit in humans. This depends on pathway redundancy, compensatory signaling, immune regulation, tissue-specific context, and a dimensionality that exceeds the scope of our training data by orders of magnitude.

Cancer cells activate resistance pathways through mechanisms we cannot enumerate exhaustively. Chronic inflammation induces immune tolerance through processes we partially understand. Neurodegenerative diseases involve protein aggregation, neuroinflammation, and synaptic loss in feedback loops we cannot yet model at therapeutic resolution.

These are not interpolations within learned space. These are emergent behaviors of complex adaptive systems. And this explains the pattern we observe: AI drug discovery efforts today announce molecules rapidly, partner enthusiastically, and fail clinically at rates that some have suggested are indistinguishable from those of traditional approaches.

The AI solved the chemistry problem. The biology problem remains unsolved because it was never within the model’s domain of competence.

VI. Generative biology: real progress, uncertain translation

But here the story bifurcates. While small molecule AI drug discovery has largely accelerated optimization without reducing attrition, generative biology has achieved technical breakthroughs that genuinely expand the possible.

AlphaFold2’s structure prediction is a capability shift beyond incremental improvement. The impact is already tangible. Crystallography and cryo-EM experiments can now be guided by predicted structures, reducing failed experiments. Mechanistic hypotheses can be tested computationally before expensive validation. Protein-protein interaction interfaces can be modeled for therapeutic intervention. AlphaFold3 extended this to protein-ligand, protein-nucleic acid, and multi-component complexes.

De novo protein design has also been validated experimentally at scales that merit attention. RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN, and related methods have generated proteins with novel folds, structures that do not exist in nature, that express in bacteria and fold as predicted. Not all predictions validate, but reported success rates of 40-60% for novel topologies represent a leap from the ~5% success rates of earlier rational design approaches.

Antibody optimization has shown measurable acceleration. Computational platforms have designed antibody variants with improved binding, reduced immunogenicity risk, and enhanced developability properties that have been validated in wet-lab experiments. Several computationally optimized antibodies are in clinical trials, though efficacy data is not yet mature.

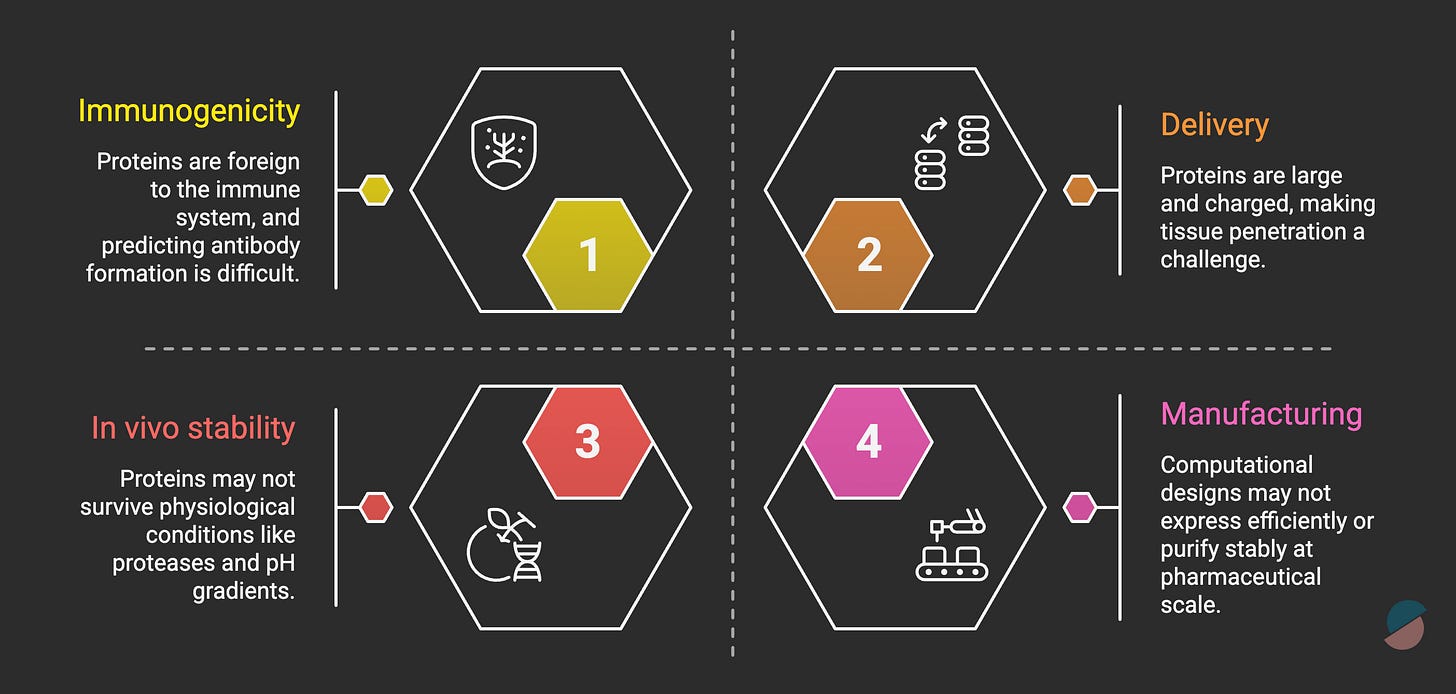

But critical limitations remain. Therapeutic efficacy in humans is unproven. The timeline to know this is 5-10 years minimum, and the challenges of protein design are formidable (figure below).

The key distinction: with therapeutic proteins, you’re engineering the drug itself, not a small molecule you hope hits the target. Target engagement is more predictable. But biological uncertainty still persists, the right target may not be the right intervention, binding may not equal efficacy, and immune responses may neutralize the therapeutic.

So what would constitute validation? Phase III readouts showing computationally designed biologics improve patient outcomes. Immunogenicity data from actual patients. Head-to-head comparisons demonstrating superiority over traditional design. Multiple successes across disease areas.

Generative biology has made genuine technical progress in protein engineering. For research tools and industrial enzymes with rapid validation cycles, the value is already evident. For diagnostics, impact is likely within 2-3 years. For therapeutics, the same regulatory and clinical validation burden applies as to everything else.

I think claiming certainty in either direction is premature. The honest position is humility paired with technical respect for what has been achieved.

VII. What would it actually take

If we are serious (and billions in deployed capital suggest some seriousness), the path forward is not more of the same on a larger scale. It is structural change in what we model and how we validate.

Shift 1. Embed first-principles as priors, not afterthoughts

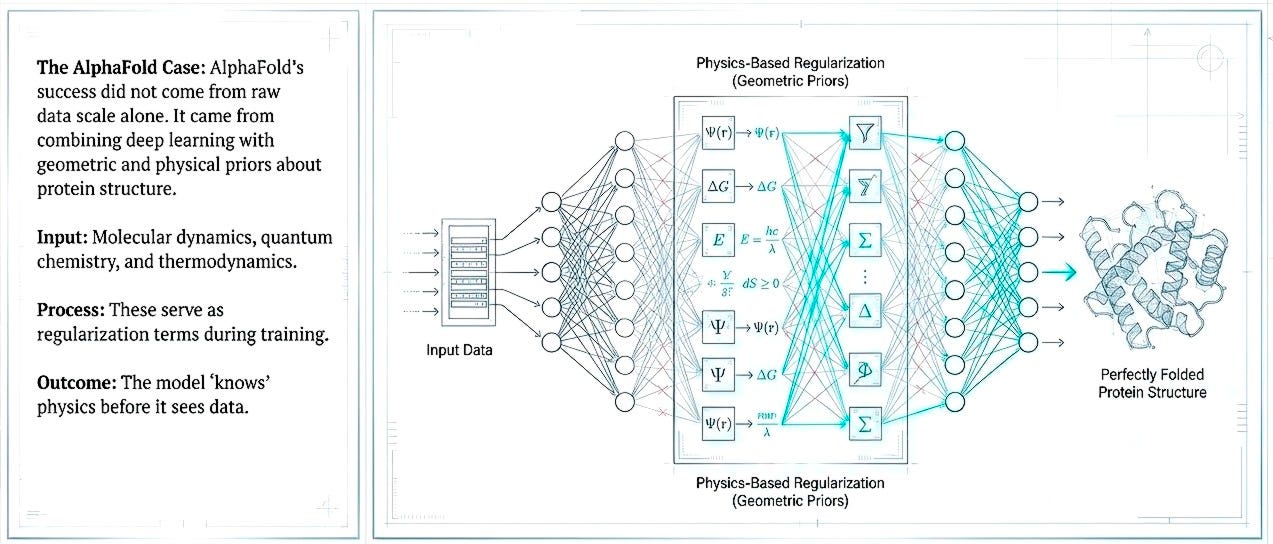

The next generation of AI discovery efforts must embed physical constraints, molecular dynamics, quantum chemistry, and thermodynamics, not as post-hoc validation but as regularization within the learning process. AlphaFold’s success came from combining deep learning with geometric and physical priors about protein structure. Pattern recognition constrained by physical law reduces the space of plausible solutions and decreases dependence on massive but biologically shallow datasets.

But structure is only one layer. The protein folds, binds a ligand, activates a pathway, then what? Each transition opens onto a larger biological possibility. We need models that traverse these scales.

Shift 2. From single targets to multiscale systems

Multiscale modeling (molecule to pathway, pathway to tissue, tissue to organism. Feedback loops, compensatory signaling, immune modulation) cannot be dismissed as “too complex.” They are the biology. Models incapable of representing them will fail to predict them.

I don’t believe these are abstract aspirations. Quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) models already simulate drug effects across physiological scales using differential equations. They are limited by incomplete biological knowledge, not computational power. The opportunity is integrating machine learning’s pattern recognition with mechanistic modeling’s causal structure.

Shift 3. From recommendation to experimentation

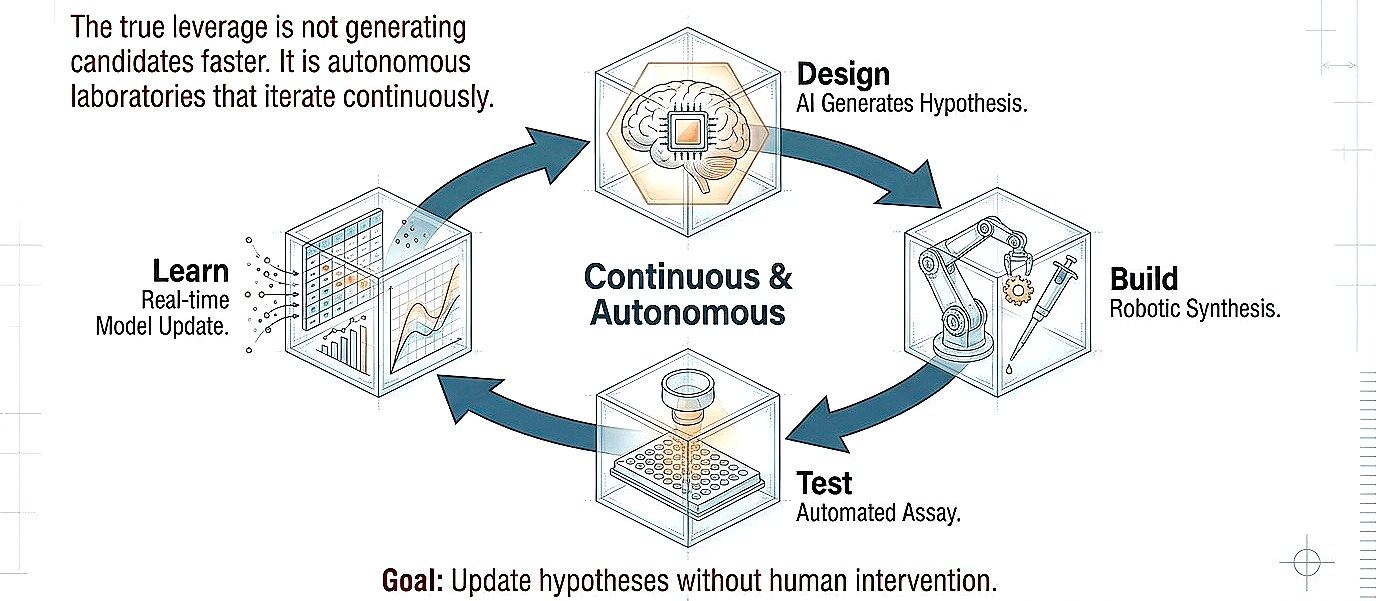

I think the true leverage is not necessarily generating candidates faster but closing the design-build-test loop at higher fidelity. Autonomous laboratories that iterate continuously, learning from failure in real-time, updating hypotheses without human bottleneck. Even with humans in the loop, the focus should shift more toward uncovering biologic effects, preferably in humans, rather than optimization in the chemical space.

This exists today only in restricted domains. Organic synthesis robots optimize reaction conditions through hundreds of iterations overnight. The same principle must extend to cell-based assays, organoid models, and eventually in vivo systems. The constraint is not computational; it is infrastructural and cultural.

Shift 4. From predicting success to predicting failure

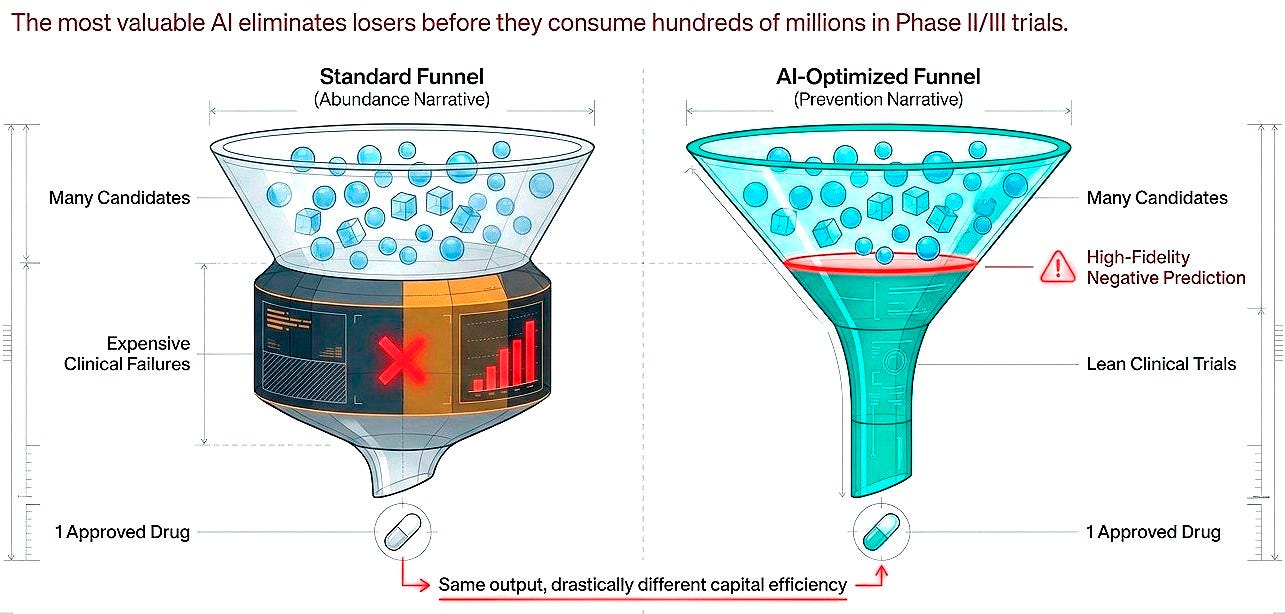

Here is the reframe that cuts through the field's marketing jargon: the value proposition is not merely about accelerating winners but about eliminating losers before they consume hundreds of millions. High-fidelity negative prediction, identifying molecules that will fail in humans based on preclinical signatures, would be worth as much as generative models producing candidates, possibly more.

This is harder to sell. Investors prefer abundance narratives over prevention narratives. But economically and scientifically, both are essential. Success in drug discovery is rare and stochastic. Failure is common and, in principle, more predictable. The current imbalance is striking: the vast majority of AI drug discovery investment flows toward generating and optimizing molecules, while comparatively little targets the systematic prediction of failure modes.

For every platform accelerating lead identification, there should be equivalent effort building models that predict clinical futility early, before Phase II consumes $50-100 million, before Phase III consumes $200-300 million. Predicting what won’t work may be less inspiring than designing what might, but it is more tractable and, at current attrition rates, quite valuable.

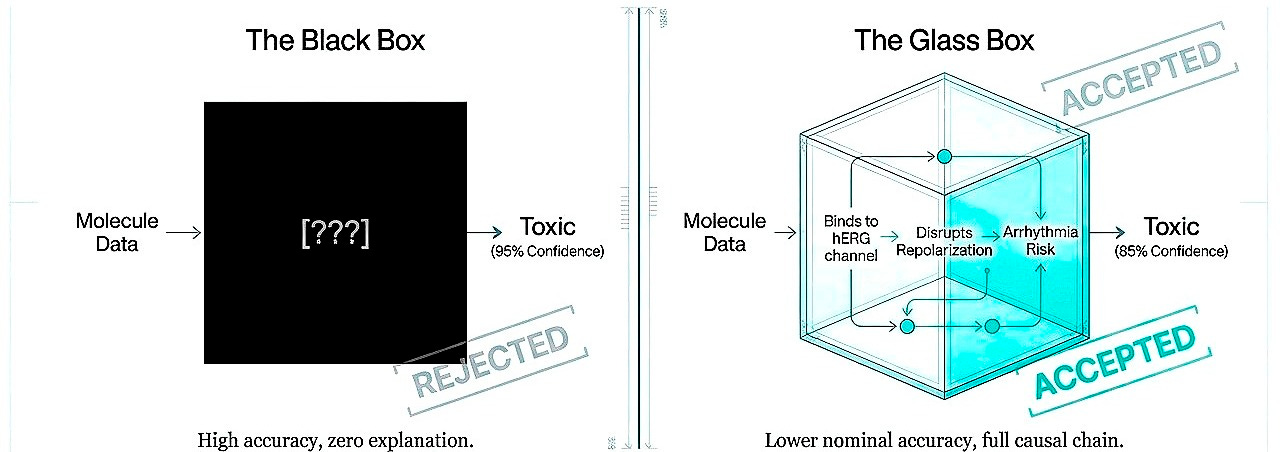

Shift 5. From black boxes to interpretable causation

Regulatory acceptance will not follow from performance alone but from understanding. A model predicting toxicity at 95% accuracy but unexplainably is less valuable than 85% accuracy with exposed causal chains. Today, interpretability is not a luxury, it is a requirement for trust.

It’s important to note that explainability is a function of human cognition, not truth. It is conceivable, perhaps inevitable, that certain biological insights will emerge from computational reasoning at scales beyond human cognitive reach. A model integrating millions of variables across molecular, cellular, and systems levels might produce predictions we cannot reduce to causal narratives, not because the model is wrong but because the biology operates through interactions too numerous and nonlinear for human intuition to hold simultaneously.

We are nowhere near that threshold. Current black boxes are not incomprehensibly sophisticated. They are insufficiently grounded. They fail to explain not because their causal chains exceed human comprehension but because they have learned no causal chains at all, only correlations that shatter outside training distributions.

I believe the path forward is stepwise, trust earned through demonstrated capability. Initially, models must expose reasoning in biological terms, this molecule inhibits hERG, this pathway has redundancy, this population lacks the biomarker. Interpretable, falsifiable, grounded. As sophistication increases, multiscale integration, higher-order interactions, full interpretability may become infeasible. At that threshold, trust shifts: prospective validation across contexts, explicit uncertainty quantification, consistency under perturbation. Regulatory frameworks will need criteria for “trustworthy opacity.”

But that evolution must be earned through reliability, not assumed through promise. The FDA does not need to understand neural architectures. It needs to know why molecules fail and whether failure could have been anticipated. Models meeting this standard will integrate into approval. Models remaining opaque without the consistent, prospective accuracy that would justify opacity will remain advisory.

The threshold for accepting unexplainability is not 95% retrospective accuracy on held-out data. It is a reliable, generalizable prediction in prospective human trials, a standard that no platform has achieved. Until AI reaches that level, interpretability may not be negotiable, even though it lowers the threshold of reality to the level of human cognition. It is the price of entry into the room where decisions about human life are made.

VIII. No shortcuts

I think the fantasy that AI would disrupt drug discovery through sheer acceleration, more molecules, faster screening, and cheaper trials, is dissolving for those paying close attention. This is because the real problem is not computational speed. It has always been, and remains, biological uncertainty.

We have made genuine progress. Targeted therapies when we understand the target. Checkpoint inhibitors when we understand immune regulation. GLP-1 agonists when we understand metabolic signaling. Protein structure prediction when we constrain the problem correctly. These successes share a pattern: they began with biological insight, not pattern recognition. The computation-optimized solutions to problems we already partially understood.

What we lack is the ability to generate that biological insight computationally. To predict which of the thousands of possible targets will matter in which diseases. To anticipate compensatory pathways before clinical failure reveals them. To simulate human response at sufficient resolution that virtual testing predicts real outcomes.

This goal, a computational model of human biology accurate enough that drugs tested in silico have comparable success probability to those tested in humans, is not incremental. We are not close. We may be halfway.

But this distance is the exciting work ahead of us. The platforms that survive will not be those with the largest datasets, fastest pipelines, or most impressive demos. They will be those that accept, early and uncomfortably (but confidently), how far we are from the goal and build toward it with rigor over spectacle.

Somewhere in the architecture of the next decade’s models, if we are disciplined, is the beginning of that simulator. It will not emerge from larger transformers trained on PubMed or fragmented data. It will emerge from physicists, immunologists, physician-scientists, and control theorists working alongside machine learning engineers, building representations that respect causation, scale, and irreducible complexity.

Until then, we have optimization. We have correlation at scale. We have infrastructure. We have genuine technical achievements in protein engineering. These are valuable, and they should be sold honestly as what they are.

What we do not have, what no platform yet possesses, is the ability to look at a molecular structure and predict with confidence whether it will improve human suffering or extend human life.

The Turing test for drug discovery is not whether AI can design a molecule indistinguishable from human work. It is whether the molecule works in humans indistinguishable from our best intent.

We are still waiting for the first machine to pass.

Well analysed and written 👏 Thanks Sean for this clear and honest review on the true current state of AI for drug R&D, and the specific opportunities that lie ahead. For the next phase, we definitely need fresh eyes and not more of the same.

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. You really nailed that point about the gap between computational eleagance and clinical efficacy. It kinda reminds me of Pilates, where a move looks perfect on paper but my body's reality is something else entirely. Super relevant for AI challenges!